Debt Aesthetics: Medium Specificity and Social Practice in the Work of Cassie Thornton

| November 25, 2018 | Posted by Webmaster under Volume 25, Number 2, January 2015 |

|

Leigh Claire La Berge (bio)

City University of New York

Dehlia Hannah (bio)

Arizona State University

Abstract

This article considers the “debt visualizations” of social practice artist Cassie Thornton. Thorton’s works use a combination of photography, performance art, sculpture, non-fiction narrative, text, and hypertext to explore the cost and consequence of the accumulation of student loans. The essay examines Thornton’s use of both traditional and non-traditional artistic materials and practices in order to articulate how the ‘immaterials’ of debt become an artistic medium; her radical departure from traditional media leads squarely back to the problem of the medium itself in Thornton’s assertion that “debt is [her] medium.” While it is tempting to read such a claim as an embrace of a “post-medium condition,” this essay argues that in our highly leveraged present, the very form of unsecured student debt that Thornton works in and on invites a return to and a reconsideration of the seemingly conservative impulses of aesthetic Modernism and its critique.

I. Introduction: Social Practice, Medium, Critique

“As I get closer to [the debt], the wind picks up. There are dead dry leaves in the air. It seems so far away, it looks like a huge pointy skyscraper, pointy, sharp at the top. It’s gray, no clouds. Farm fields surround it, the ground here is dewy, bare, with short dead grass. I’m completely alone” (Thornton).[1] So begins the text of one of the visual artist Cassie Thornton’s “debt visualizations,” in which Thornton uses “debt as a medium” so that it would be “materialized,” “collectivized,” and would “change forms.” Working in and on her own debt and that of her family and colleagues, Thornton’s art uses a combination of photography, performance art, sculpture, non-fiction narrative, text, and hypertext to explore the cost and consequence of the accumulation of private and government-subsidized student loans (Thornton). In the case of Thornton herself, the better part of this debt was obtained while studying for a Masters of Fine Arts (MFA) degree at the California College of the Arts, where she received her MFA in 2012 in the relatively new field of “social practice.”

In this issue of Postmodern Culture on “intermediality, immediacy and mediation,” we explore Thornton’s use of both traditional and non-traditional artistic materials and practices in order to articulate how the “immaterials” of debt are constituted through her work as an artistic medium. In calling the socio-economic conditions of artistic production and exhibition into service as the substrate of art itself, Thornton follows in a long tradition of modern and contemporary art practice, particularly that of institutional critique. From Hans Haacke’s detailing of the alleged real estate holdings of the Museum of Modern Art trustees in his Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 to Michael Asher’s placement of the sales office directly within the exhibition space of the Claire Copley Gallery in 1974, artists have long turned a critical gaze on the infrastructural world that supports them. These institutions, in turn, have learned to assimilate such critique, and eventually, to welcome it in the form of artists’ residencies (Fraser).[2] In this context, W.J.T. Mitchell’s expansion of the definition of medium to include “not just the canvas and the paint … but the stretcher and the studio, the gallery, the museum, the collector, and the dealer-critic system” is apt—and yet it leaves out a crucial condition of possibility for the creation and circulation of artworks, namely the cost of training as an artist (198).

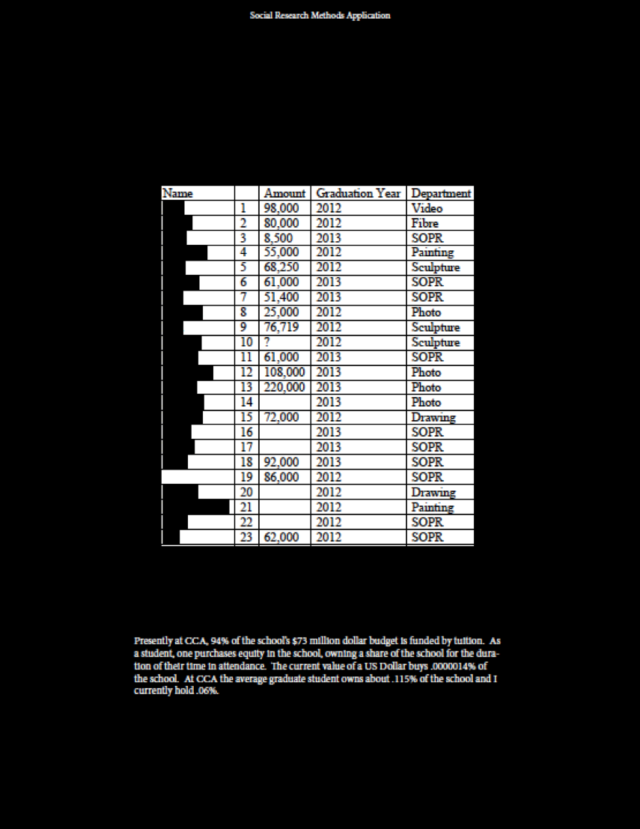

Thornton locates her critical practice within a highly ambivalent site of artistic infrastructure: the financial scene of the MFA program, that odd, leveraged, and vaguely shameful gateway to artistic professionalization.[3] Indeed, there may be no truer instantiation of the old McLuhanite maxim that “the medium is the message” than Thornton’s insistence that art students “make art and debt.” Thornton estimates her graduating MFA class will produce and absorb about 3.2 million dollars of student debt. (See image, page 5). What Thornton’s work demonstrates is that even as art students are being trained to work in various mediums and to circulate their work through an art world increasingly exposed as imbricated in its conceptual and economic structure into the circuits of contemporary capitalism, they are all the while implicitly training and being trained in the making of debt and in living, working, and creating art in a condition of indebtedness. [4] Whatever other medium and form it may take, much of contemporary art is thoroughly mediated by a financial scene in which the matter of accumulation finds a necessary correlate in a condition of indebtedness. It is debt as a site of mediation through Thornton’s use of debt as medium that we seek to illuminate in this paper.

Fig. 1. Cassie Thornton, Application to London School of Economics (2012) (Debt Owed by the 2012 Graduating MFA Class of the California College of Art, Page 18, Courtesy of the Artist; SOPR is an abbreviation for “Social Practice”). Provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

Disclosing the elusive formal structures of debt and its distinctive affective, aesthetic, and political potential as a medium seems to require recourse to a multiplicity of artistic strategies embedded within more familiar materials and immaterials. Rosalind Krauss contends that “the abandonment of the specific medium spells the death of serious art”; we contend that only through the abandonment of specific, traditional mediums does the emergence of a new medium with its own conceptual, material, and social specificity become possible (Perpetual 33).

For this operation to be legible in contemporary arts discourse, Thornton’s work must first be situated in the context of an emergent aesthetic mode, one designated by its practitioners, theorists, and nascent degree-granting programs as “social practice.”[5] Deeply in conversation with a critical tradition first articulated by Nicholas Bourriaud in his 1998 Relational Aesthetics, social practice artwork places its emphasis on the work of art’s ability to intercede into a delimited social world of economic exploitation, including those relations that adhere to the such as feelings of belonging unequal distribution and accumulation of material resources such as wealth, as well as to immaterial recourses and respect. Such an orientation immediately changes what constitutes the work of art itself, and Bourriaud identifies what have come to be called relational artworks and social practice artworks as those whose “substrate is intersubjectivity.” In contrast to traditional modes of artistic practice in which one speaks of the visual, musical or plastic form of artworks, or of the readymade or performance art, Bourriaud urges that we concern ourselves with “formations” and argues that in “present-day art shows that form only exists in the encounter and in the dynamic relationship enjoyed by an artistic proposition with other formations, artistic or otherwise” (21). While it is no doubt correct to claim that “all good artists are socially engaged,” what differentiates social practice as a mode is that its engagement with scenes of economic and affective inequality is executed with specific attention toward some sense of restitution or recognition (Deller qtd. in Bishop, Artificial 2).[6] The social formation achieved through the work, then, marks a possible configuration of the world and of affects and experiences therein, one which, though itself transient, models and stimulates iteration and variation upon the same. Through such work, it becomes possible to explore the intersubjective relations and relations to objects and institutions that constitute the implicit forms of everyday life.

This theoretical tradition inherited from Bourriaud has transformed into a still-expanding theoretical compendium that instructs how, precisely, we should categorize and critique what we might now refer to as social practice art works. The mode’s theoretical proponents include, most recently, Shannon Jackson, who argues in Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics that such works’ theatricality is a site of “medium unspecificity,” and includes exegeses on artists ranging from William Pope L. to the Creative Time organization.[7] Almost simultaneously, Claire Bishop published Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and The Politics of Spectatorship, a modification and contextualization of her earlier critique of what she calls “participatory art” as, among other things, deriving from a “creative misreading of post-structuralist theory” in which “rather than the interpretations of a work of art being open to continual reassessment, the work of art itself is argued to be in perpetual flux” (“Antagonism” 52).[8] Bishop’s other concerns include these works’ focus on “ethics,” their overly ameliorative forms of sociality, their abandonment of modernist paradigms of discomfort, and, most interestingly for our purposes, a worry that such works are positioned unselfconsciously and homologously in relationship to the transition from a commodity-based economy to a service-based economy, and likewise from a curation of objects to a curation of subjects and subjectivity.[9]

Our particular focus will be this final link between social practice artwork and what many social theorists (no less than art historians) have argued is the contemporary disaggregation of the social itself. We believe that Thornton’s work might begin a conversation about the relationship between form, medium and our current economy that some have called “late,” others “neoliberal” and, most persuasively in our view, others “financialized.”[10] We maintain, then, a focus on the economic throughout and assume that if value is, as Marx said, a social relation, then debt might be understood to telescope a particular experience of that relationality in our financialized present.[11] Thornton’s work both concretizes and aestheticizes this necessary relationality and renders debt as what Dick Bryan, Randy Martin, and Mike Rafferty have called a “lived abstraction,” one that we take as a never completed but embodied and experiential concretization of capital’s dimension of abstract value (465).

Our concern in this essay, then, is to obtain a level of economic specificity through Thornton’s debt-as-medium specificity and to explore what level of mediation is appropriate for an arts-production and arts-history system that is the most sensitive and responsive to the logic of capitalism in the academic humanities. It is not enough to acknowledge this fact, as countless critics do.[12] To return to the ur-example of a modernist critique of medium, would a truly “expanded field” of paint not take critics beyond the canvasses of abstract expressionism and into the oil fields and refineries from which the material of paint itself derives?[13] Indeed, once we, as critics, have embraced the concept of the expanded field, it becomes possible to address phenomena such debt that exist concretely only within the myriad of institutional, material, personal, and social spaces comprehended by the post-medium condition. The expanded field makes it possible to consider the specificity of a newly available or newly workable medium.

II. Invest in Yourself: Unsecured Debt and Aesthetic Reflexivity

There is a long tradition of Marxist critique of commodity aesthetics and capital aesthetics, and now an emergent tradition outside of Marxist theory that Walter Benn Michaels has recently called neoliberal aesthetics.[14] Within this divergent theoretical context we aim to articulate a problem of “debt aesthetics” that we believe is particularly germane to social practice artwork and its professionalization and institutionalization. To theorize a debt aesthetics, however, one must begin with some theorization of debt. As a result of the 2007–8 subprime mortgage crisis and the subsequent expansion of that crisis into a global credit contraction and “Great Recession,” the language of debt has entered the public imaginary through reportage, fiction, and, not least of all, individual experience. It has entered social scientific academic discourse in the work of a new generation of social theorists including David Graeber, Miranda Joseph, Richard Dienst and Mauricio Lazzarato, while Fred Moten has sought to articulate together the language of Kantian aesthetics, structural racism, and mortgage debt with his wonderfully titled paper “The Subprime and the Beautiful” (Eschavez See, fn.1). A more activist site of engagement and theorization has emerged in the Berkeley-based journal Reclamations and through the Strike Debt campaign and its 2012 Debt Resistors’ Operations Manual, both of which have devoted attention to student debt and discussed its salience for the current generation of undergraduates, graduate students, and young professionals.

In each of these works, “debt” itself becomes unmoored from the familiar Marxist vocabulary of commodity, money, capital, and value in order to be re-articulated as a disciplinary apparatus of temporal and spatial organization and an omnipresent site of ongoing psychic investment and divestment. For this reason, it should not be surprising that anthropology no less than economics and political economy has played a particularly important role in elaborating our understanding of debt as a lived social relation and in emphasizing that quotidian practice should be the ground on which debt’s theoretical architecture is built.[15] This type of attention to the lived experience of debt is also foundational to our understanding of debt aesthetics as manifested in, and, we hope, able to be extrapolated from, Thornton’s work. Indeed, we are in a critical moment in which debt seems to have become conceptually differentiated from the panoply of concepts that have sustained economically-oriented cultural criticism—whether artistic, literary, or social-historical—such as the commodity, value, and capital.[16] It is too soon to judge whether this attempt will be successful. For example, it remains a real question whether, as so often happens, it makes sense under any conceptual regime to articulate the United States government’s national debt together with individual debt. One tension of this article, and of Thornton’s concept of “debt as medium,” is to take medium as a well-developed arts concept and put it into experiential and material dialogue with an emergent proto-concept of debt. In both cases, however, the simple representation of debt is not sufficient.

From the Frankfurt School through the work of Fredric Jameson, Marxist aesthetic criticism and economically-oriented criticism more generally have centered on the commodity with careful attention to the exposition of its form. Walter Benjamin, for example, emphasizes the tension between the cult value and exhibition value of art, a dichotomy derived from the use value and exchange value of the commodity.[17] Theodor Adorno refers to the fetish character of music as a musical work assumes the commodity form and circulates accordingly (288-317). But debt, as one element of a structure that Marx calls “interest-bearing capital,” operates according to a different economic logic, one that evades habitual apprehension and therefore becomes generative of a different aesthetics and different forms of criticism. Marx writes that in contradistinction to the classic capitalist exchange of M-C-M’ [Money-Commodity-Money’], “[i]n interest-bearing capital, the capital relationship reaches its most superficial and fetishized form. Here we have M-M’, money that produces more money, self-valorizing value, without the process that mediates the two extremes” (Capital: Volume III 515). Marx offers us a clue into the aesthetics of interest-bearing capital when he suggests that “[i]n M-M’ we have the irrational form of capital, the misrepresentation and objectification of the relations of production, in its highest power” (516).[18] Debt may be seen as a particular species of what La Berge has called elsewhere a “financial form,” an economic instantiation that requires specific attention to temporality, to appearance, indeed to an aesthetics of capital reconstituting itself through interest as it seems to expand automatically in a highly mediated fashion (274).

How then does debt appear and disappear, how is it recognized and misrecognized in aesthetic discourse? Perhaps because its formal structure has not been analyzed and historicized like that of the commodity, debt gets scant theoretical attention in the rare mentions of it in art criticism. Indeed, debt tends more often to be understood as an abstract and metaphorical concern rather than a concrete and economic one. Hal Foster and Yve-Alain Bois worry that “if artists become indebted to their situation they become finite — impotential” (100). While Foster and Bois are attentive to a state of indebtedness as a constraint on critical and aesthetic flourishing, we soon realize that the form of indebtedness they are concerned with is not literal. They continue:

Debt to the situation translates into a sense of “responsibility,” like the artist who today finds him/herself in the midst of a capitalism in crisis—nothing new there!—and is compelled to make art out of a sense of pathos and guilt rather than affirmation. Aesthetic production becomes hopelessly derivative and mimetic in the worst sense of the operation. It becomes positivist rather than appropriative. And it is against this general weakness that we have thought of a fundamental question for artistic pedagogy—naturally, many others remain buried beneath the surface. The question is: how to change the classroom so that it will produce subjects (artistic, political, scientific)? (100)

There is high irony in the fact that Foster and Bois deploy the language of debt and capitalist crisis to highlight a lack of aesthetic autonomy, a particularly modernist concern. Indeed, they go so far as to venture into the practice and structure of artistic education without noting that for most apprentices, debt first and foremost takes the form of a responsibility to repay student loans. Their use of debt as a metaphor, as an entry into a Badiouian situation, shows the elasticity of debt as a proto concept, but also reveals the importance for critics in distinguishing when debt functions as a metaphor and when it functions as a substance.

In his much-cited The Making of the Indebted Man, Lazzarato himself deploys debt as both a metaphor and a concept. He labels it “an archetype of social relations” that, through the course of his treatise, becomes endowed with ever-greater philosophical if not economic specificity (33). “Debt constitutes the most deterritorialized and the most general power relation through which the neoliberal power bloc institutes its class struggle,” he writes (89). Deleuze, too, in his now-famous comment that has been used to mark the historical transition from a Fordist to a financial regime of accumulation (“man is no longer a man confined but a man in debt” [181]) was not referring to deferred payment or to money loaned at interest, but to a temporal extension of the well-known problem of capitalist enclosure. What even these brief treatments suggest is that debt’s multidisciplinary and multi-modal presence could benefit from conceptual differentiation and specification and, we believe, both affective and aesthetic specificity as well. Indeed, in Thornton’s case, the affective and the aesthetic are inseparable.

Thornton’s effort to produce medium specificity through a mode of relational social practice, we argue, can be transposed into economic specificity and contribute to an emerging debt literature as well as to debates on mediality in a new medium ecology. The term “debt aesthetics” is meant to engage debt as a “lived abstraction”; it is meant to locate how debt as an abstraction and how debt as a metaphor can be reconnected to its substance. In working through Thornton’s archive of debt visualizations, performances, sculptures, texts and hypertexts, we are working through economic specificity and medium specificity simultaneously. Thornton’s chosen medium is debt, but it serves our critical purposes to identify what kind of debt it is. The type of debt we are concerned with is the unsecured student loan, which possesses several distinctive properties. First, in contrast to all other forms of debt except back taxes owed to the federal government, whether it is given by a state or private lender, student loan debt may never be absolved or forgiven through bankruptcy.[19] Second, the loans’ interest rates may fluctuate with changing laws. And finally, the debt is initially backed by the United States government, which pays the interest as long as the debtor is enrolled in an accredited educational institution, but which ceases to do so once the debtor leaves that institution. Perhaps most importantly, the debt is labeled “unsecured” because there is no collateral.

One method of puncturing the odd spatial and temporal presence and absence, the seemingly abstract quality of any debt, is to consider what it is indexed to. With a secured loan, there is an object that serves as collateral: a car loan refers to a car, a home mortgage a house, and so on. Student debt and medical debt are somewhat different in this regard insofar as they are indexed to a process or experience rather than an object. This final property of unsecured debt creates a peculiar set of constraints and possibilities that the Chicago School economist Gary Becker captures well through his elaboration of “human capital,” that sum total of economic possibility contained within each individual:

If I invest in my human capital, I cannot in modern societies use my capital as collateral to borrow loans. That’s why we have such a poorly developed commercial market for loans and investments. You look at student loans: they’ve developed extensively in the United States because of the government guarantee and subsidy to student loans…. [I]f I buy a house, I can give my house as mortgage. If I don’t make my payments, they take my house away from me, as we’re seeing all these foreclosures going on now. I can’t give myself as collateral. Now, in the past with slavery and other forms of indentured servitude you could do that. In modern society we’ve ruled that out, for good reasons I think. And so you can’t do that, and I think it makes it very difficult for poor people who don’t have other forms of capital to invest in themselves. (14)[20]

Becker writes from a position of critique: how should “poor people” be able to invest the assets that accrue to their human capital, those drives and capabilities that are unique to their person? What if, for example, student loans were calibrated to individuals as they are to small businesses, to potential career paths, SAT scores and so on? Becker’s utopian hope for expanded opportunities of self-investment contains the obvious corollary—already perceptible in his allusion to mortgage—that under his scheme individuals would necessarily have expanded and personalized opportunities for indebtedness. Furthermore, the startling political implications of investing in oneself become obvious in Becker’s quasi-nostalgic references to slavery and indentured servitude. It seems that his concern is that these legal institutions and categories of personhood have been retired without being replaced by something comparable. What is missing from Becker’s account, however, is an understanding of the social and psychic discipline that debt exerts on its subjects and of how indebtedness is internalized through self-investment. Lazzarato, by recourse to Nietzsche, provides a crucial corrective to our understanding of unsecured debt, in particular, when he claims that “the creditor-debtor relationship is inextricably an economy and an ‘ethics’ since it presupposes, in order for the debtor to stand as a ‘self’-guarantor, an ethico-political process of constructing a subjectivity” (49).

Education, like medical care, transforms the individual at a particular point in time, and, if all goes as planned, this transformation is retained over time in the form of health, skills, cultural capital, pedigree, professional networks and so forth. And while some have floated the idea that academic degrees should be rescinded for reason of default on student loans, it is clearly impossible to repossess the forms of personal development and opportunity that education promises and may have already delivered. While a degree, like a house or a car, is acquired, education is internalized. Unsecured debt, then, is indexed to the person of the debtor, but it is not ‘secured’ thereby because it cannot be extracted by anyone but the debtor herself—and she too may well find herself unable to capitalize on her investment. In lieu of wielding the threat of extracting compulsory labor from the body of the debtor in the form of a contemporary debtor’s prison, the infrastructure that grants and supports unsecured debt prepares subjects to repay their loans, Thornton will suggest, through other affective means. It is no surprise, then, that the accrual of student debt should produce particular kinds of affects and experiences, other forms of personal transformation attendant upon those promised by education itself. Moreover, if art is at least to some degree an expression of the artist’s inner states, as R.G. Collingwood and Benedetto Croce argue, for example, then we should look for the traces of debt subjectification especially in the work of artists laboring under the burden of student loans. These forms of subjectification constitute the site and the medium of Thornton’s social practice, which, we recall from Bourriaud, takes intersubjectivity as its substrate. When Thornton invites her fellow students to visualize and articulate their debt, to bring it to psychic consciousness and give it aesthetic form, she brings the lived abstraction of unsecured debt newly to life, as it were, in the domain of the aesthetic.

The aesthetics that result from employing that unsecured debt as a medium reflect the formal properties of this type of debt in a peculiar manner. In thinking about medium specificity, we want for the moment simply to mark the reflexive structure of unsecured debt as a site of self-investment, self-loss, and potentially of individual and collective self-transformation. This makes debt a particularly interesting candidate as a medium—but it does not make it a medium. For artistic practice to concern itself with and to exhibit the specificity of a medium—rather than merely to be beholden to its constraints and possibilities—the properties of the medium must be wrought in and through aesthetic form. In moving from making art in debt to making art out of debt, or from working in debt to working on debt, Thornton seeks to use debt against itself, to explore its properties, to grant to this persistently misrecognized and obfuscated immaterial new forms of visibility, sensibility and comprehensibility. And indeed her explorations of these unspoken experiences shared by art students disclose unexpected qualities, metaphors and sites of malleability in the lived abstraction of unsecured debt. Ultimately, Thornton will reveal debt aesthetics to be suspended between modernist reflexivity, as the problem of self-investment quickly becomes a problem of self-reflection, and contemporary romanticism, for the project of university education remains a romantic one despite the new economic toll it exacts. Yet whereas romanticism in its first iteration was reactionary, in this particular instantiation it seems able to dwell almost seamlessly beside its object of critique.

III. Application to London School of Economics

Following in the lead of contemporary practitioners of institutional critique, during her final year of study for her MFA at the California College of the Arts (CAA) Thornton tried to obtain an artist’s residency in the college’s financial aid office. The letters that she wrote recommending herself for this position and her proposals for artistic intervention came to be part of her Master’s Thesis, a far more ambitious project eponymously titled Application to London School of Economics. Although the unsolicited application was unsuccessful in its manifest aim of obtaining an artist’s residency, Thornton’s application is testimony to her multifaceted approach to rendering unsecured debt accessible and malleable as a medium of art. Application includes documentation of Thornton’s social and multi-media practices including personal narratives of her own life, institutional correspondence, graphs, charts, photographs, appropriated images and content from other artists, and the text of what Thornton has come to call “debt visualizations,” which she performed with members of her graduating class. The 53-page artist’s book extends into digital space where additional debt visualizations and associated images are collected on Thornton’s website.

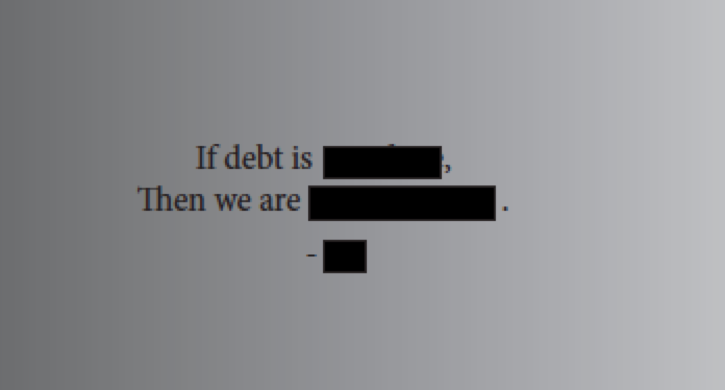

Perhaps the most immediately striking feature of Application is that much of its content is blacked out, as though sensitive information had been redacted. On the first page of Application (Figure 2), we are introduced to an ambiguous constellation of visual, textual and structural elements that undergird the debt aesthetic that Application develops.

Fig. 2. Cassie Thornton, Cover Page from Application to London School of Economics (2012). Provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

The book performs a persistent and agonizing negotiation of the representability of debt’s form and content. The refusal or impossibility of representation is also continually refigured in Application, reflecting the structure of unsecured debt. How does a debtor who does not have a job comprehend a debt of $84,000? How is such a debt located in space and time? Or how does that debt configure the debtor’s sense of space and time? Most crucially, Application investigates whether the affect that the indebted situation engenders can be discharged even if the debt itself cannot.

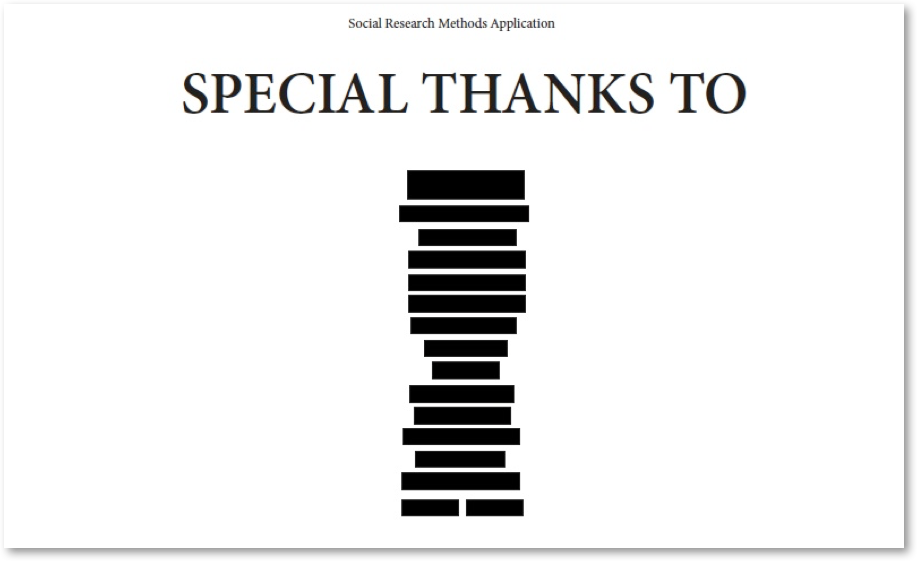

Application begins by explaining itself: “I have declined the opportunity to use the formal application as my current research, which I hope to continue during the residency, adheres to strategies that require that I interact with all institutional communities using alternative logic and methods representative of my experimental practices, including this application process” (2). Thornton explains both the generic character of social practice artwork and her creative endeavor to “reveal a hidden logic central to the economic relationship in educational institutions of all types” (2). The play between disclosing and performing hidden logics continues as the artist thanks her collaborators and supporters in this project (image three):

Fig. 3. Cassie Thornton, “Special Thanks,” Application to London School of Economics p. 4 (2012). Provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

Thornton then moves jarringly from official (if nonetheless imploring) prose to first-person narration, positioning herself in a network of debtors along familiar lines of twenty-first century economic precarity. She describes how loss of health insurance results in medical debt for one parent while stagnant wages and periods of unemployment generate credit card debt for the other. She recounts her own passage through the global credit contraction caused by the American housing bubble and subprime mortgage crisis, in which low interest rates and predatory lending created an opportunity for her family to accumulate a home and an outsized mortgage, only to be quickly followed by foreclosure and bankruptcy. And finally, there are Thornton’s own debts, small debts incurred to pay for emergency flights home to attend to family members in crisis, and the looming debt for an arts education that inflects her writing style with a lilting, associative quality and her dreams with images of rocks and sculptures by Carl Andre. Every facet of social reproduction in Thornton’s orbit, it seems, transpires through a matrix of debt and indebtedness. Some of these debts began as sites of genuine hope, even utopian potential—a hope that still flickers in the form of her MFA and gives the thesis project a kind of urgency, even a desperation, that is disconcerting because it deprives the reader of any comfortable vantage point of aesthetic disinterest. Could there be a better liberal, humanist “self-investment” for “poor people,” in Becker’s words, than an education? Could there be a more reasonable or normative hope for stability than that of owning one’s own home?

In her evocative personal history, found in a section dryly but not ironically titled “Financial History,” one gets the sense that Thornton is making a profound effort to convey her experience in a manner that, if not factually complete, warmly invites the reader into her personal world. Her disclosures contrast the black-block redactions that appear on most of the book’s pages and visually limit the viewer’s access to information, and they stand in tension with the provocations and evasions in which Thornton is clearly engaged in her correspondence with the institutional authorities at CCA. The shifts between openness and opacity and between visual and textual modes of communication create a readerly text the proto-narrative structure of which entrains the viewer to complete. And yet, one does not know whether to fill in the gaps with images, texts, economic data, or psychological speculation. The uneven and mixed media expand an imaginary of debt into multiple registers and one begins to comprehend how consuming it may be to live this capitalist abstraction.

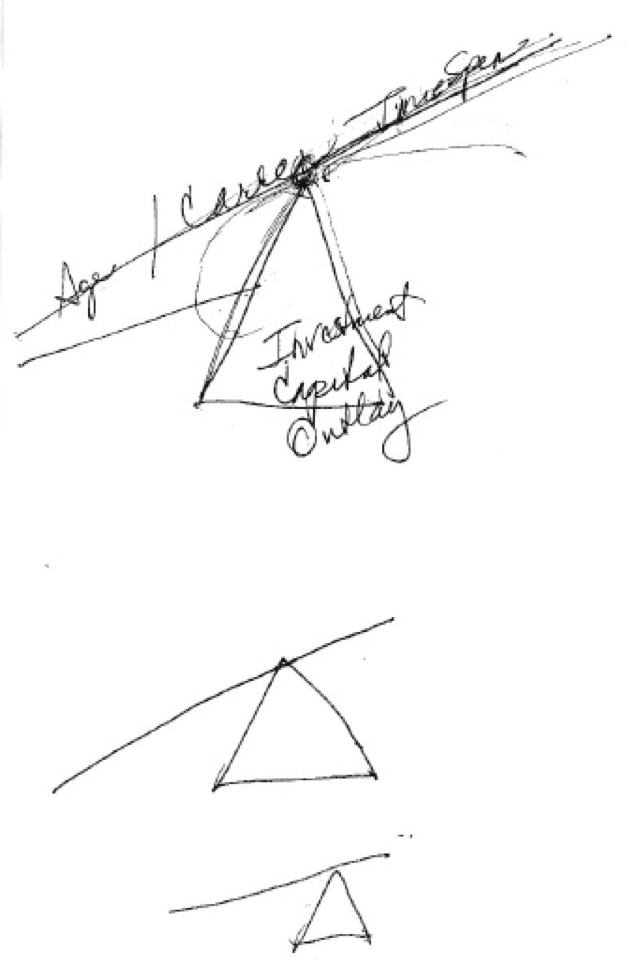

In order to understand the implications of her own debt, Thornton consults a certified financial planner, and we are privy to the planner’s analysis. As “someone who loves you [Thornton],” the anonymous financial planner writes, “I think it’s great that you’re creating images/visual experience around debt. I wish more people would do this.” The planner continues: “many people’s ‘ships’ are dangerously close to icebergs and they don’t have a clue!” The planner’s own visualization (Figure 4), what the planner herself refers to as “scribbles,” is designed to help the debtor decide what the ratio of productive to unproductive debt is in the debtor’s portfolio and where, in the particular case of Thornton, her education should be considered on the spectrum:

So, from a purely analytical standpoint, we need to consider what your capitalized lifetime earnings are anticipated to be both WITH and WITHOUT your Master’s Degree from CCA. Based on our discussion and your estimates, it looks like over a 33 year career (allowing an initial two years to get your bearings or “foot in the door”) that you may conservatively earn about $600,000 more than if you did not complete your Master’s. Using a discount rate equivalent to the inflation assumption I used of 3.5%, on a present value basis, this equals $180,000. Because your Graduate School component of your debt, and in fact, all remaining student loans, total about $100,000, we can legitimately categorize this debt as “productive”. YEAH! (21)

With the financial planner’s help, we are led to understand that Thornton’s net worth might be about $80,000 more over the course of her career than it would have been had she not invested in herself by obtaining an MFA. By the time a photograph of an iceberg appears in the final pages of Thornton’s book, the reader is likely to have missed or forgotten the financial planner’s explicit analogy of the frozen mass with financial danger. Instead, the reader will have come to associate its shape and texture with the rocks, imaginary objects, and sculptures with which Thornton compounds our associations with debt.

Fig. 4. Financial Planner’s “Fulcrum Drawings” showing age, career and time span balanced on the fulcrum of interest, capital, outlay. Cassie Thornton, Application to London School of Economics (2012) Page 20. Provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

A series of conceptual and visual tropes emerge alongside Thornton’s narrative which fracture Application’s sense of plot and direction. There is a feeling of both energy and enervation; of trying to “transform the material of debt” and of being unable to locate a social space in which such a transformation would be possible. An association emerges of debt as an imposition, an omnipresence whose impenetrability is both psychic and physical. But Thornton struggles against this idea to present debt as constitutive of a shared reality that might potentially be intercepted and reorganized: “once its material form is identified, there is hope that the debt may be harvested and used as a pedagogical, social, and fiscal resource,” she writes (Application 19).

As fitting of a social practice artwork, one of the most distinctive formal features of Thornton’s Application is its affective charge. The work’s affect is a mixture of inviting openness and intimacy with all willing to share in her utopian aspirations for debt as medium alongside as aggressive pursuit of those reluctant to become involved in her project. With a mixture of sincerity and aggression Thornton takes her appeal to restructure student debt to the director of the Social Practice program. She writes, “I’m anxious to hear your perspective on Social Practice and its many forms of social exchange in relation to the capitalist mechanism. As always, I appreciate your enthusiasm for unorthodox thought when everything seems doomed to utilitarianism. I’ll swing by your office. Best! Cassie” (50). The contraction of “I will” and the exclamation point render her anxiousness friendly and intimate; at the same time, if the director had repeatedly told her “no”—and he had, we have read the correspondence—then why does she insist on casually swinging by his office? One might almost say that Thornton repurposes the affect of a debt collector’s telephone presence: friendly and persistent, seeking all information and any form of contact because contact and positive identification of the debtor hold open a space for continued contact. While the time period during which a debt remains active in the USA differs by state, all that is required to keep it active is for the collector to maintain contact within that period, ranging from 3 to 7 years. Being hounded by debt collectors is not just their approach to collecting, but of keeping the debt alive and extending its futurity.

Ultimately Application and Thornton’s practice itself cohere around the debt visualizations that she conducts with her cohort of MFA students. She explains the process using a vocabulary appropriate to the plastic arts: “I am in the process of interviewing every MFA student about the financial liabilities they’ve accrued while attending CCA. Each is asked to describe the essence of their debt as an expression of texture, aura, scale, material composition, etc, from within a meditative state” (32). In a private space ritually purified by the burning of sage, Thornton invites her fellow debtors to free-associate on the word “debt” and to imagine approaching their debts from a distance. What results from these dialogues is a new verbal, visual—and specifically art historical—aesthetic discourse through which MFA students trace their paths to artistic professionalization and indebtedness. As the possibility of individual debt enabled each of them to pursue an MFA, so the possibility of collectivizing debt in a shared aesthetic imaginary enables Thornton to mold and sculpt, indeed we might say to begin to ‘restructure’ the subjective (if not the objective) conditions of their cumulative debt burden.

Despite Application’s attempts to literalize and concretize, a new metaphor does emerge prominently from its collection of debt visualizations. Certain images and tropes appear so often that they come to seem generic. Debt is heavy, vast, terrifying; it is almost always looming but not necessarily present. But what is perhaps most surprising is that during their debt-visualization sessions, indebted MFA students produced recurring references to and images resembling the work of the post-minimalist sculptor Richard Serra. In one sense, it is rather unremarkable that the debt visualizations of MFA students would generate images and anxieties tied to successful, practicing artists. But the force of the association is nonetheless striking.

“There is an imponderable vastness to weight,” Serra once commented, in reference to his own work (138). As Thornton suggests in her analysis of this trend of debt-induced Serra associations, students’ unsecured debt—like Serra’s sculptures—always seem on the verge of collapsing, and yet these terrifying, precarious objects somehow endure through space and time. Indeed Serra’s emerging presence in Application may lead the viewer to look back at the “Fulcrum Drawings” scribbled by the certified financial planner with new attention. They could be reread as a study for a work such as Serra’s Trip Hammer (1988), in which one steel slab balances atop another, stabilized only by the precise angle and distribution of the weight of each component.

The size of the fulcrum is important. While a properly-sized fulcrum can provide the added lift or leverage to catapult you to the next level, if it is too large, you may just slide back down. In other words, if your debt is too large for the projected return, it could act as a weight instead of a level and pull you down (below where you would have been had you not taken on the debt in the first place). (Financial planner; Thornton, Application 21)

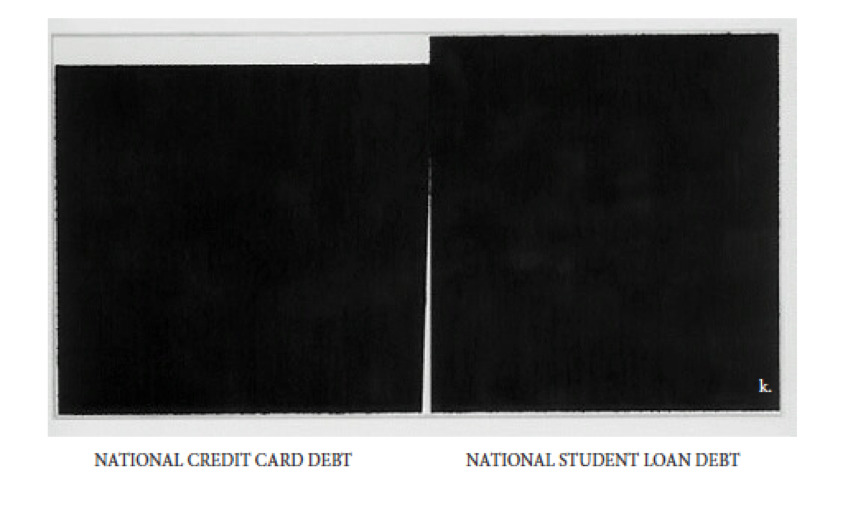

In light of such associations, we might be tempted to retroactively read Serra’s works as debt visualizations. We might also start to see Thornton’s own use of black squares and rectangles throughout her text in a different light.

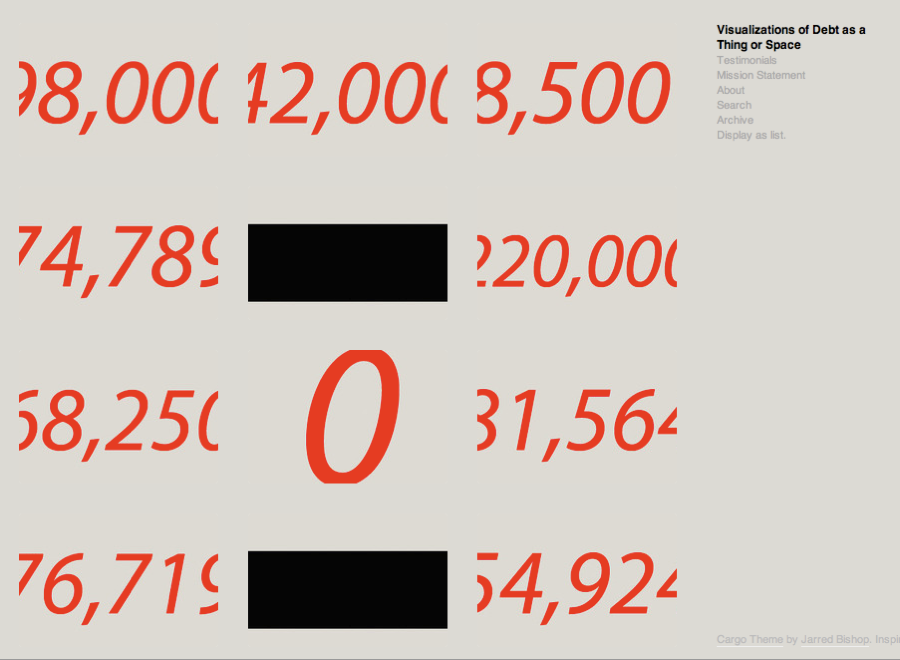

Thornton is particularly drawn to Serra’s oil-stick drawings, which she incorporates into her ever-capacious debt aesthetic by offering gallery tours of Serra’s work and appropriating images of Serra’s The United States Government Destroys Art (1989) to serve as an economic graph comparing credit card and student loan debt (Figure 6). When asked why he worked at one end of the color spectrum, Serra explained: “from chartreuse to pink inevitably leads to metaphors that deflect attention elsewhere and take you away from the graphicness of drawing…[but black’s] main association is to writing and printing, and to drawing. If it represents anything, [black] represents graphicness” (qtd. in White, Rose and Garrels 82-83). In the new context of Thornton’s work, however, black acquires other associations: both those of anonymity as well as to the financial vernacular phrase “in the black.” When a ledger is “in the black” it registers profit; when it is “in the red,” it registers loss. In the image below (Figure 5) from Thornton’s website, each red number indicates an amount of student debt; clicking on the number links to the text of the debt visualization of said debtor. Clicking on a black bar also takes the viewer to a debt visualization, but in these cases the redaction of the numerical “amount” owed doubles as a visual metaphor for the obtrusive and impenetrable burden of the debt.

Fig. 5. “Visualizations of Debt as a Thing of Space,” courtesy of Cassie Thornton (http://debt-visualizations.tumblr.com/). Provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

In an exercise reminiscent of the concrete poetry of Carl Andre and Robert Smithson, Thornton presents one particular debt visualization as a kind of poetic form in which the line breaks of the text ‘sculpt’ its content. The halting, interrupting, repetitive content of the language suggests the inability of this MFA student to speak or think linearly about his or her unsecured debt, while the poem’s form evokes debt as a workable three dimensional substance:

debt is

future self is paying

“future” dad is paying

her son, will he pay to play ex post facto?

what is the motivation to pay

after the value is used up?

the value of the mfa is my life

hard to imagine not doing it,

doesn’t want to imagine regretting it

it’s weird that it has a monetary value

the life has a trail of debt

heart races when

she passes the debt on the street

there is a murky cloudiness,

a wall coming out of it

over her head

NO!

Richard Serra steel and leaning

instead of a sky,

it’s a steel plate sloping down (38)

For this debtor too, encountering his or her debt through visualization is like encountering a Serra sculpture: one must walk around it and, in doing so, one’s perspective continues to change as every new angle and vantage point offers the opportunity to begin again. But the content, the sculpture itself, remains massive and unmoving.

In order to differentiate the representation of debt from its use as a medium, one can place Thornton’s debt visualizations in a dialectical relationship to the large-format photographs of various global stock-trading floors that Andreas Gursky has produced. We now know that the traders who populate Gursky’s images may well have been trading the kind of unsecured debt that Thornton has and sculpts. But the iconic representation of stock-based scenes of financialization and its effects both obscures and forecloses the opportunity to participate in the social relations that are constitutive of the forms of value manipulated therein. Thornton’s social practice of sculpting affective and intersubjective relationships, by contrast, intervenes in and on the material substrate of a financialized economy much as post-minimalist sculpture operated upon the detritus of a post-industrial one.

Post-minimalist practice, and Serra’s work in particular, presciently aestheticized and memorialized the detritus of an economy that was becoming newly post-industrial. Throughout the late 1960s and early 70s, post-minimalist practice repurposed materials of steel, oil, blighted urban space, privatized and empty corporate space, asphalt, concrete and so on to mark aesthetically the economic transition away from a Fordist economy.[21] By introducing Serra into Application, Thornton introduces some crucial if necessarily speculative questions: what constitutes, or what will constitute, the detritus of a financialized economy whose vectors of value veer between financial transactions in the upper echelons and a deskilled, service-based economy that relies on the production and exchange of affects and experiences, including the experience of education itself, in its lower echelons?[22] And what aesthetic mode and artistic medium will best engage this economy? Thornton cannot answer these questions, but she does hint at a relational triangle between an older economic formation and its avant-garde and a new economic formation still waiting for its own aesthetic. She does so by engaging in an unexpected move of debt-bricolage and Serra, too, becomes interpolated into Thornton’s community of debtors. The debt visualizations not only disclose his work and general aesthetic as a trope for debt that resonates widely among her fellow students; Thornton actually attempts to entrain Serra into her project via a letter she mails to him that she includes in her book, a copy of which she also has surreptitiously left on Serra’s kitchen table in his New York City townhouse by anonymous, an art handler whom she knows (personal communication with the artist).[23] Much as debt collectors call family members or anyone who might have access to a debtor, or any collateral that could be given in its place, Thornton renders Serra almost guilty by aesthetic association. The reference to Tilted Arc (1981), a public sculpture commissioned for and then removed from Federal Plaza in New York City after eight long years of rancorous debate, is the height of irony. While Serra and his supporters claimed that the sculpture was successful in heightening viewers’ attention to their own movement through the space, critics decried it as a rusty eyesore, a magnet for rats and bombs, and most pertinent to our discussion, a gross obstacle to public use of the plaza. Thornton’s appropriation of the sculpture as a means to heightening awareness of debt in the public consciousness redeems both positions.

As with her entreaties to her own financial aid office, Thornton’s invitation to Serra was duly rebuffed. Like a debtor avoiding a collection agency, Serra knew that the best response is no response. Indefatigable, Thornton appropriated another of Serra’s works (Figure 6). As part of the performative aspect of her Application, Thornton became licensed as a docent and lead tours of the 2012 Richard Serra Drawings retrospective that serendipitously happened to be on exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Thornton titled this part of her project “Urgent Debt Tour of Richard Serra Drawing Show” (Figure 7). As Michelle White explains in her catalogue essay of the show (from which exhibition the next two images of Thornton’s are taken), Serra’s drawings are “about the intangibility of conceptual thought and the visceral immediacy of direct physicality” (White, Rose and Garrels 14). This understanding of Serra’s work could be transposed onto Thornton’s conception of debt, and indeed, Figures 6 and 7 invite the reader to do just that. Thus we are introduced to yet another site of aesthetic debt and indebtedness. What Thornton’s work leaves us with is the sense that such bricolage and entraining of the figures of the art world could continue ad infinitum, or at least as long as the relationship between art as value and art as expression is one that is simultaneously cemented and jettisoned by the institutional world of art. This includes the places where Serra’s work is seen and sold as well as the art schools where students are trained and impoverished.

Fig. 6. Cassie Thornton, National Credit Card Debt vs. National Student Loan Debt (2012). Provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

Fig. 7. Cassie Thornton, “Urgent Richard Serra Debt Tour”; in background, Richard Serra, The United States Government Destroys Art (1989) (oil-stick drawing). Photograph provided by the Feminist Economics Department (the FED).

IV. Conclusion

Rosalind Krauss noted that “Serra’s sculpture is about sculpture” (Perpetual 127).[24] With this Modernist claim we want to return to one of the central concerns of this paper, hinted at but unsubstantiated until now: namely, that unsecured debt as a radically new and seemingly post-medium medium returns us to some of the traditional problems of medium specificity. How, ultimately, does unsecured debt develop its modernistic, aesthetic reflexivity? It follows a logic Marx already laid out in his discussion of nineteenth-century public debt: “As with the stroke of an enchanter’s wand, [the public debt] endows unproductive money with the power of creation and thus turns it into capital” (Capital: Volume I 919). In the course of accumulated unsecured debt, however, money is turned not into capital but into critique.

One of the criticisms of so much debt activism is that debt, particularly debt accumulated in the course of post-graduate liberal and fine-arts education, is in part the product of a sense of entitlement. If Thornton did not want the debt, after all, why did she pursue an arts degree, of all things? That question needs to be answered in both structural and individual terms. Structurally, of course, like Serra’s One Ton Prop (House of Cards) (1969), capitalism itself falls apart without a system of mass indebtedness (although historically debt has been distributed in different temporal and spatial forms). Individually, however, Thornton did feel “entitled” not only to go into debt, but to transform that debt into something else through the site specificity of the scene of its accumulation. And it is through the site specificity of the debt—accrued in an MFA granting institution that specializes in social practice—that we arrive at the ultimate reflexivity of debt as a medium. It was only by going into more unsecured debt for her MFA that her undergraduate student debt could be endowed with the reflexivity required of a Modernist medium. In other words, her MFA debt is both cause and object of her ability to formalize indebtedness as a medium. Thornton’s debt is about debt.

Footnotes

[1] All citations from Cassandra Thornton, “Application to London School of Economics.” All links and images used by permission. Thornton’s work was on view at “To Have and To Owe” at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in New York City, Sept. 22 – Oct. 21, 2012, curated by Leigh Claire La Berge and Laurel Ptak. Documentation available at http://to-have-and-to-owe.tumblr.com.

[2] Consider, for example, Fraser’s own “Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk” (1989), delivered at the invitation of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Fred Wilson’s critical curatorial work at the Maryland Historical Society for “Mining the Museum” (1992–93); and Mark Dion’s residencies at the London Museum of Natural History, the American Philosophical Society and other institutions.

[3] See Singerman for a history of the MFA program. In a different context, see McGurl for a history of writing MFA programs. Neither work discusses the integral role of student loans and thus student debt in the institutional history of the MFA program.

[4] See Williams.

[5] Thornton’s own institution defines social practice as that which “incorporates art strategies as diverse as urban interventions, utopian proposals, guerrilla architecture, ‘new genre’ public art, social sculpture, project-based community practice, interactive media, service dispersals, and street performance. The field focuses on topics such as aesthetics, ethics, collaboration, persona, media strategies, and social activism, issues that are central to artworks and projects that cross into public and social spheres. These varied forms of public strategy are linked critically through theories of relational art, social formation, pluralism, and democracy. Artists working within these modalities either choose to co-create their work with a specific audience or propose critical interventions within existing social systems that inspire debate or catalyze social exchange.” (From https://www.cca.edu/academics/graduate/social-practice). In 2012, Portland State University launched a journal devoted exclusively to social practice artwork in connection with its own MFA program.

[6] See the long footnote on 287 for the full quotation.

[7] Shannon Jackson, Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics (Routledge, 2011). For Creative Time see Nato Thompson’s Living as Form (MIT, 2012).

[8] While both Jackson and Bishop make reference to social practice, they themselves do not use the term to categorize the works they discuss, preferring instead their own idioms. That all of these works, as Jackson herself notes, rely on tropes of theatricality and performativity is surely important to the situation of interpersonal relationality. Both Jackson and Bishop provide their own versions of a genealogy from relational aesthetics to the present: for Jackson’s see 46–48; for Bishop see 2–3. We use the term “social practice” because Thornton uses it, and because her MFA program, in many ways her object of critique, does so as well. For a popular overview of the term, see Kennedy.

[9] “In other words, the contemporary university seems increasingly to train subjects for life under global capitalism, initiating students into a lifetime of debt, while coercing staff into ever more burdensome forms of administrative accountability and disciplinary monitoring. More than ever, education is a core ‘ideological state apparatus’ through which lives are shaped and managed to dance in step with the dominant tune” (Bishop, Artificial Hells 269).

[10] See also Friday, Joselit, and Klobowski.

[11] As always in discussing Marx, it is crucial to differentiate value from profit. We are concerned with the former. For an explication of the structure of both, see Postone.

[12] For example, Rosalind Krauss does on the first page of “Reinventing the Medium,” when she notes that “[t]his essay was written on commission by the DG Bank in Munich for the catalog of its collection of twentieth-century photography” (289).

[13] Originally defined by Krauss: “The expanded field is thus generated by problematizing the set of oppositions between which the modernist category sculpture is suspended. And once this has happened, once one is able to think one’s way into this expansion, there are logically three other categories that one can envision, all of them a condition of the field itself, and none of them assimilable to sculpture” (“Sculpture” 38).

[14] See, for example, Benn Michaels.

[15] Graeber is the obvious candidate here. But see also Roitman.

[16] A concept is, broadly speaking, “a formulation through which [one] makes sense of [her] object of inquiry.” It might be distinguished from an analytic, defined as the choice of inquiry or more basically, a theme. We would argue that the work of “debt studies,” or Thornton’s work however one designates it (indeed this article and our proto-concept of debt aesthetics), is an exploration of the potential of debt to become fully conceptualized. For a clear exposition of the difference between analytic and concept, see Koopman and Matza.

[17] One could name many other works that take the commodity as their subject, a central form of cultural and aesthetic analysis. See, for example, Ross; McClintock; Harvey; and Jameson.

[18] This ceaseless reconstitution through interest suggests to Marx that the “fiscal system contains within itself a germ of automatic progression” (515).

[19] See Collinge.

[20] From an edited transcript of a conversation held at The University of Chicago on May 9, 2012. The video recording of the open seminar can be viewed on-line at http://vimeo.com/43984248. It may seem odd to find Gary Becker here where one might expect to find Nietzsche, but, as the transcript of this conversation reveals, he is in deep sympathy with Michel Foucault on the constitution of neoliberalism. When asked what he thought of Foucault’s lectures on Biopolitics Becker said “I don’t disagree with much” (3). Foucault himself had turned to Becker’s work to articulate his own genealogy of Ordo and Neoliberalism. See Foucault.

[21] For a good overview of some of the econometrics of this transition, see Krippner.

[22] For the classic articulation of this see Sassen. Bishop considers a similar point in her discussion of Bourriaud: “It is important to emphasize, however, that Bourriaud does not regard relational aesthetics to be simply a theory of interactive art. He considers it to be a means of locating contemporary practice within the culture at large: relational art is seen as a direct response to the shift from a goods to a service-based economy. It is also seen as a response to the virtual relationships of the Internet and globalization, which on the one hand have prompted a desire for more physical and face-to-face interaction between people, while on the other have inspired artists to adopt a do-it-yourself (DIY) approach and model their own ‘possible universes’” (“Antagonism” 54).

[23] She writes to him, “Dear Mr. Serra,…your forms represent an omnipresent debt to us, or vice versa…[and] there is a sense that on the way to becoming an artist of your stature we are encouraged to acquire debt.” Thornton goes on to suggest that he collaborate with her cohort of indebted students by auctioning off one of his pieces, “but now referring to it as representation of debt—donating some proceeds to the class. (I was thinking of one of the pieces that have been removed or have gone unused, like a part of Tilted Arc.)” (Application 37).

[24] The full quotation reads “Richard Serra’s sculpture is about sculpture: about the weight, the extension, the density and the opacity of matter, and about the promise of the sculptural project to break through that opacity with systems which will make the work’s structure both transparent to itself and to the viewer who looks on from outside.”

Works Cited

- Adorno, Theodor W. “On the Fetish Character of Music and the Regression in Listening.” Essays on Music. Ed. Richard Leppert. Trans. Susan H. Gillespie. U of California P, 2002: 288-317. Print.

- Becker, Gary, François Ewald and Bernard Harcourt. “‘Becker on Ewald on Foucault on Becker’: American Neoliberalism and Michel Foucault’s 1979 Birth of Biopolitics Lectures.” 2012. MS. Web. 19 Jan. 2016.

- Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002. Print.

- Benn Michaels, Walter. “Neoliberal Aesthetics: Fried, Rancière and the Form of the Photograph.” Nonsite.org 1 (2011). Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October 110 (2004): 51-79. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- —. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso, 2012. Print.

- Bois, Yve-Alain, Hal Foster, David Joselit, et. al. “Recessional Aesthetics: An Exchange.” October 135 (2011): 93-116. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. Nicolas Bourriaud: Relational Aesthetics. Presses Du Reel, 2002. Print.

- Bryan, Dick, Randy Martin and Mike Rafferty. “Financialization and Marx: Giving Labor and Capital a Financial Makeover.” Review of Radical Political Economics 41.4 (2009): 458-472. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Collinge, Alan. The Student Loan Scam: The Most Oppressive Debt in U.S. History – and How We Can Fight Back. Beacon P, 2009. Print.

- Deleuze, Gilles. Negotiations. New York: Columbia UP, 1995. Print.

- Dienst, Richard. The Bonds of Debt. Verso, 2011. Print.

- Echavez See, Sarita. “Gambling with Debt: Lessons from the Illiterate.” American Quarterly 64.3 (2012): 495-513. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College De France, 1978-1979. Trans. Graham Burchell. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Print.

- Fraser, Andrea. “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique.” Artforum 44.1 (2005): 278-285. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Friday, Matthew, David Joselit, Silvia Klobowski. “Roundtable: The Social Artwork.” OCTOBER 142 (2012): 74-85. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Graeber, David. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Melville House, 2011. Print.

- Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Wiley-Blackwell, 1991. Print.

- Jackson, Shannon. Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics. Routledge, 2011. Print.

- Jameson, Fredric. The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983-1998. Verso, 1998. Print.

- Joseph, Miranda. A Debt to Society. U of Minnesota P, 2014. Print.

- Kennedy, Randy. “Outside the Citadel, Social Practice Art is Intended to Nurture.” New York Times 20 Mar. 2013. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Koopman, Colin and Tomas Matza. “Putting Foucault to Work: Analytic and Concept in Foucaultian Inquiry.” Critical Inquiry 39.4 (2013): 817-840. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Krauss, Rosalind E. “Reinventing the Medium.” Critical Inquiry 25.2 (1999): 289-305. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- —. Perpetual Inventory. MIT P, 2010. Print.

- —. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October 8 (1979): 30-44. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Foster, Hal and Gordon Hughes, eds. October Files: Richard Serra. MIT P, 2000. Print.

- Krippner, Greta R. “The Financialization of the American Economy” Socio-Economic Review 3.2 (2005): 173 –208. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- La Berge, Leigh Claire. “The Men Who Make the Killings: American Psycho, Financial Masculinity, and 1980s Financial Print Culture.” Studies in American Fiction 37.2 (2010): 273-296. Web. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Lazzarato, Maurizio. The Making of the Indebted Man: An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition. Trans. Joshua David Jordan. Semiotext(e), 2012. Print.

- Marx, Karl. Capital: Volume I. Trans. Ben Fowkes. Penguin, 1976. Print.

- —. Capital: Volume III. Trans. David Fernbach. New York: Penguin, 1981. Print.

- McGurl, Mark. The Program Era. Cambridge: Harvard, 2009. Print.

- McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. Routledge, 1995. Print.

- Mitchell, W.J.T. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. U of Chicago P, 2006. Print.

- Postone, Moishe. Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory. Cambridge UP, 1993. Print.

- Roitman, Janet. Fiscal Disobedience: An Anthropology of Economic Regulation in Central Africa. Princeton UP, 2004. Print.

- Ross, Kristin. Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture. MIT P, 1996. Print.

- Sassen, Saskia. Globalization and Its Discontents: Essays on the New Mobility of People and Money. New Press, 1999. Print.

- Serra, Richard. Drawing a Retrospective. Menil Collection. Distributed by Yale UP, 2011. Print.

- Singerman, Howard. Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University. Berkeley: U of California P, 1999. Print.

- Thompson, Nato. Living as Form. MIT P, 2012. Print.

- Thornton, Cassandra. “Application to London School of Economics.” MFA Thesis. California College of the Arts, 2012. Web. 2 Mar. 2013.

- White, Michelle, Bernice Rose and Gary Garrels, eds. Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective. The Menil Collection, 2011. Print.

- Williams, Jeffrey. “The Pedagogy of Debt.” College Literature 33.4 (2006): 155-169. Web. 1 Mar. 2013.