Sensorimotor Collapse? Deleuze and the Practice of Cinema

| November 18, 2018 | Posted by Webmaster under Volume 25, Number 2, January 2015 |

|

Timothy Bewes (bio)

Brown University

Abstract

This essay discusses the central historical proposition of Gilles Deleuze’s cinema books, the “sensorimotor break” that separates the classical cinema of the movement-image from the modern cinema of the time-image. That proposition is more or less in line with dominant accounts of the politics of periodization in twentieth-century aesthetics. Jacques Rancière’s thought offers a powerful challenge to any such notion of a break or rupture, and Rancière pays particular critical attention to Deleuze’s work on cinema. A work by the Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi (The Mirror) is introduced in order to show up some shortcomings of Rancière’s critique insofar as it impacts Deleuze’s project, and to illustrate the difference between understanding cinema as a medium of thought and as a practice.

Mediators are fundamental. Creation is all about mediators. Without them nothing happens. They can be people—for a philosopher, artists or scientists; for a scientist, philosophers or artists—but things too, even plants or animals … Whether they’re real or imaginary, animate or inanimate, you have to form your mediators. It’s a series. If you’re not in some series, even a completely imaginary one, you’re lost. I need my mediators to express myself, and they’d never express themselves without me: you’re always working in a group, even when you seem to be on your own.

Gilles Deleuze (Negotiations 125).

The status of the medium in Gilles Deleuze’s thought is far from straightforward. On one hand, mediators are necessary, indeed irreducible. Neither thought nor ideas are possible without them. “Ideas have to be treated like potentials already engaged in one mode of expression or another and inseparable from the mode of expression, such that I cannot say that I have an idea in general” (“What is the Creative Act” 312). On the other hand, no idea is transferable from one medium to another. “Ideas in cinema can only be cinematographic” (316). For all their irreducibility, media do not function as vehicles for ideas. The importance Deleuze attaches to the ‘mediator’ should be understood as a departure from the concept of medium. Mediators, he says, are “fundamental”—no longer intermediary but primary (Negotiations 125). To conceive of cinema, say, as a mediator is quite unlike seeing it as a medium or a form. Cinema’s concepts, writes Deleuze, “are not given in cinema. And yet they are cinema’s concepts, not theories about cinema” (Cinema 2 280). Statements like these in Deleuze’s work raise many questions, for the ideas of a work seem thereby to be both wrested away from the form in which they become thinkable and returned to it.

A cinematographic idea, according to Deleuze, is frequently an event of disconnection. As such, a cinematographic idea is less an idea than a collapse or disturbance of the links that make nameable, attributable, applicable ideas possible. Take, for example, the dissociation of speech and image, an effect explored in the cinematic work of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, or Marguerite Duras, which effects “a veritable transformation of elements at the level of cinema” (“What is the Creative Act?” 319). Where does such an idea take place: in the technical apparatus itself or in the choices and decisions of the filmmaker? In the thought of the theorist or scholar who documents it or in the historical forces and conditions that determine its appearance? Such questions refocus our attention on the problem of the medium and its relation to thought.

This essay addresses these concerns mainly in the context of Deleuze’s work on cinema. However, the case of the novel stands as a constant backdrop to this discussion, for the novel is a form in which the question of the relation between idea and medium is easily forgotten and is often ignored by critics – no doubt because of the linguistic basis of the material, which encourages the assumption that the novel is an unproblematic form for the transmission of ideas. Three questions that Deleuze raises in his work on cinema have particular significance for the context of the novel: (i) Is a distinctively cinematic thought possible? (ii) If so, how should we understand the historical dimensions of its emergence? And (iii) what is, or what can be, the role of the critic or philosopher with respect to that thought? These questions have as much relevance to contemporary literary studies as to cinema, and yet – again, because of the material qualities peculiar to literature – they rarely come into focus as a central concern of literary critics. Yet Deleuze’s work on cinema makes possible and necessary a theoretical attentiveness to the novel as a mode of thought; indeed, a working assumption of this essay is that the implications of Deleuze’s cinema books for the novel are as profound and far-reaching as any work of novel theory since the founding contributions of thinkers such as Georg Lukács and Mikhail Bakhtin. Such implications will be especially apparent insofar as there is a historical, rather than medium-specific, argument to Deleuze’s work on cinema. This essay, therefore, will primarily engage the second of the three questions listed above (although the other two are indissociable from it). How should we understand the historical claim of the emergence of a distinctively cinematic thought? What, in other words, is entailed for thought by the proposition of a “sensorimotor collapse”?

The most contentious idea in Deleuze’s writings on cinema is also its central organizing principle: the “sensorimotor break” that separates the classical cinema of the movement-image from the modern cinema of the time-image. “The link between man and the world is broken,” writes Deleuze (Cinema 2 177). But what is the historical status of this break? And what is its relationship to the narratives that are sometimes put forward to explain developments in twentieth-century literature and aesthetics which have generally been understood in terms of a historical shift from realist, representative modes to non-realist, non-representative ones? If the sensorimotor break is a development specific to cinema, its historical significance will be that of a merely formal (i.e., technological or subjective) development. If, on the contrary, the sensorimotor break describes a historical shift, a transformation of consciousness, then it must be detectable in other forms also, including literature, painting and music.

Certainly, the quandaries that Deleuze’s proposition of a sensorimotor break puts us in as critics seem readily transferable to the literary context. Mikhail Bakhtin’s early work on Dostoevsky, for example, invites the question of whether Bakhtin (the theorist) or Dostoevsky (the writer) is the real originator of the concept of polyphony. That is to say, is the collapse of the “monologically perceived and understood world” in Dostoevsky’s works a historical event, anticipated by Dostoevsky in a prophetic vein as Bakhtin claimed (7, 285), or is it an effect peculiar to his aesthetic intentions? Similarly, is the supposed “meaninglessness” of Samuel Beckett’s work “one that … developed historically,” as Adorno insisted (153), or a merely aesthetic conceit specific to the world of the writer? Is Beckett’s meaninglessness, in other words, the result of an especially acute historical sense or a deficient one? And what kind of principles do such works call on the critic to adopt: an urgent, compensatory historicism, or a spirited refusal of what Nietzsche called the “historical sense” (“On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” 63), a refusal that might have equal claim to historicity?

Such questions take on particular resonance in the context of Deleuze’s work on cinema and the shift from the cinema of the movement-image to that of the time-image, a shift that Deleuze conceptualizes using Henri Bergson’s concept of the sensorimotor schema. According to Deleuze, this shift, which he presents as a break in the links between action, perception and affection, takes place at different historical moments, depending on the economic and political circumstances of the national cinema in question. In Italy, for example, the shift happens immediately after the war with the “neo-realism” of Vittorio de Sica and Roberto Rossellini; in France it happens in the late 1950s and early 1960s with the “new wave,” and in Germany it takes place with the “new German cinema” of the early 1970s. In different ways, the pre-war films of Yasujiro Ozu in Japan and the early works of Orson Welles in Hollywood “foreshadow” these developments (Negotiations 59). Even these small differences in chronology, however, open up a tension or a quandary in the historical thesis of the sensorimotor break. For Deleuze’s explanations for the temporal discrepancies appear to restore the sensorimotor links at the very moment of their rupture; indeed, those explanations might be said to draw on a relatively conventional conception of ideology. France, says Deleuze, “had, at the end of the war, the historical and political ambition to belong fully to the circle of victors”; hence the cinematographic image initially “found itself kept within the framework of a traditional action-image, at the service of a properly French ‘dream’” (Cinema 1 211). In Italy, there was no possibility of claiming the status of victor, and yet the institution of cinema had largely escaped the influence of fascism, even during the war. Thus cinema was able to “begin again from zero, questioning afresh all the accepted facts of the American tradition” (211–12). In Germany, neither of these crucial conditions was met, and so the change there took place a decade later than in France.

Consequently, perhaps, Deleuze does not seem entirely comfortable with the historical dimensions of his thesis, such that at certain moments he disavows them. The strongest such statement is found in the preface to the French edition of The Movement-Image: “This study is not a history of the cinema. It is a taxonomy, an attempt at the classification of images and signs” (xiv).[i]

The recent work of Jacques Rancière affords a good opportunity to revisit the historical dimensions of Deleuze’s thesis for a number of reasons. In several essays, most notably in his book Film Fables, Rancière explicitly rejects the historical claims of Deleuze’s work on cinema—and yet he does so in the context of an analysis that offers as lucid an account of that project as we have anywhere. Rancière’s critique is thus difficult to dismiss on the grounds of a failure of understanding or a shortfall in interpretive subtlety. More substantively, Rancière’s recent work on aesthetics constitutes the most significant challenge to the notion of a general break or rupture in twentieth-century literature and culture, a notion that has been so much a part of critical thinking about the century.

For Rancière, the crucial event in the modern evolution of literature is not the collapse of realism, the shift from modernity to postmodernity, or “disturbances” in the sensorimotor schema noted by Deleuze, but the appearance of “literature” as such: the moment, 200 years ago in Europe, when literature became capable of saying anything, on the condition that its utterances would no longer have transmissible significance or referential value. The terms in which Rancière conceptualizes this event, however, are remarkably similar to Deleuze’s theorization of the sensorimotor break. Consider the following two passages, the first from Deleuze’s Cinema 1, the second from Rancière’s essay “The Politics of Literature”:

The crisis which has shaken the action image has depended on many factors which only had their full effect after the war, some of which were social, economic, political, moral and others more internal to art, to literature and to the cinema in particular. We might mention, in no particular order, the war and its consequences, the unsteadiness of the “American Dream” in all its aspects, the new consciousness of minorities, the rise and inflation of images both in the external world and in people’s minds, the influence on the cinema of the new modes of narrative with which literature had experimented, the crisis of Hollywood and its old genres. Certainly, people continue to make SAS and ASA [narrative driven] films: the greatest commercial successes always take that route, but the soul of the cinema no longer does … We hardly believe any longer that a global situation can give rise to an action which is capable of modifying it—no more than we believe that an action can force a situation to disclose itself, even partially. The most “healthy” illusions fall. The first things to be compromised everywhere are the linkages of situation-action, action-reaction, excitation-response, in short, the sensory-motor links which produced the action-image. Realism, despite all its violence—or rather with all its violence which remains sensory-motor—is oblivious to this new state of things where the synsigns disperse and the indices become confused. We need new signs. A new kind of image is born that one can attempt to identify in the post-war American cinema, outside Hollywood. (Cinema 1 206)

This is where the historic novelty introduced by the term “literature” lies: not in a particular language but in a new way of linking the sayable and the visible, words and things. This is what was at stake in the attack mounted by the champions of classic belles-lettres on Flaubert, but also on all the artisans of the new practice of the art of writing known as literature. These innovators had, the critics said, lost the sense of human action and significance. That was a way of saying that they had lost the sense of a certain sort of action and a certain way of linking action and significance. (Politics of Literature 9)

Rancière is not talking about the transition from realism to modernism, or from modernism to postmodernism, but the appearance of the “regime” of literature around the turn of the nineteenth century, a specific form of writing that emerges at the same time as—and as part of—the aesthetic, displacing what Rancière calls the “representative regime.” For Rancière, then, the break or crisis of narrative links occurs not with modernism, and certainly not with postmodernism. If it takes place within cinema, it is nothing other than a repetition of the earlier break in European thought that marked the appearance of the aesthetic as such.[ii] From this moment, art and literature are determined by new conditions that constitutively limit their referential (sensorimotor) function. In the work of writers such as Flaubert, Balzac, and later Proust, literature stages a relationship between two logics. The first is that of “the collapse of the system of differences that allowed the social hierarchies to be represented” (Politics of Literature 21); that is to say, of the old regime in which literary activity was constrained by appropriate subject matter and circumscribed rules of access to literary discourse. The arrival of the order of “literature” brings that system to an end. Realism, for Rancière, is thus not the form that is broken with, but the form that effects the break. Rancière describes this quality of realism in “Literary Misunderstanding” as follows:

“Realist” proliferation of beings and things signifies the opposite of what the age of Barthes and Sartre would see it as. It marks the ruin of the all that was in harmony with the stability of the social body … For the critic, Flaubert is a writer for a time where everything is on the same plane and where everything has to be described …. (Politics of Literature 39)

The second logic is that of interpretation, which presupposes the existence of a “true” level of meaning that requires the critic to “tunnel into the depths of society.” Modern hermeneutical technologies such as Marxism and psychoanalysis are entirely implicated in the modern literary regime, since their explanatory models are derived from literature itself.

The Sensorimotor Hypothesis

In order to put Rancière’s critique into dialogue with Deleuze’s hypothesis of the sensorimotor break, a closer examination of the latter is necessary. Deleuze’s cinema books appear to advance a kind of historical thesis that is unknown elsewhere in Deleuze’s work. This thesis turns on the proposition of a transition from the analysis of the movement-image, in Cinema 1, to that of the time-image in Cinema 2; and a corresponding historical evolution from the classical cinema, in which time is subordinated to movement, to the modern cinema in which we see a situation of time liberated from that subordination to movement. Thus, works such as Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero or Ozu’s Late Spring or Antonioni’s Eclipse are transitional works in Deleuze’s terms. They mark the beginning of what Deleuze calls the “upheaval” (Cinema 2 1) or “collapse” (128) of the sensorimotor system organized around the three important elements of the movement-image: perception, action and affection. The challenge that this hypothesis raises for us is twofold.

First is the question of the relation that Deleuze is attempting to envisage between cinema and philosophy. Is cinema an illustration of a certain historical process that transcends cinema (that might equally be articulated, for example, in Bergson, or Hegel); or is it, on the contrary, the realization or even the agent of that process? This is also the question of the philosophical substance of Deleuze’s thesis. But what is the relation between the historical thesis and the philosophical one? Another way of putting this question is to ask: how do we reconcile the detailed knowledge of cinema in Deleuze’s work—the anatomization or “typology” of various types of signs and images that we encounter in it—with the set of philosophical theses concerning time, movement, duration, subjectivity, etc.? Regarded separately, both aspects of Deleuze’s thinking are relatively accessible. If one knows the films he is talking about, Deleuze’s analyses of scenes and sequences are often dazzling. Likewise, Deleuze’s reading of Bergson and the adaptation of his thought in the context of cinema are philosophically compelling and rewarding. But the relation between the two is much more enigmatic.

Second is the question of the sensorimotor collapse: how, where, and why does this take place? Does it actually “take place” at all? What does it mean to say, for example, that “we no longer believe in this world”? Who is Deleuze’s “we,” and which two periods of history are divided by this “no longer”? He goes on: “We do not even believe in the events which happen to us, love, death, as if they only half concerned us. … The link between man and the world is broken. Henceforth, this link must become an object of belief … Only belief in the world can reconnect man to what he sees and hears. The cinema must film, not the world, but belief in this world, our only link …” (Cinema 2 171–2)?[iii]

Let’s consider these problems one at a time.

1. History or Philosophy?

The relation between the historical and philosophical dimensions of Deleuze’s argument is stated explicitly on the last page of Cinema 2:

Cinema’s concepts are not given in cinema. And yet they are cinema’s concepts, not theories about cinema. So that there is always a time, midday-midnight, when we must no longer ask ourselves, ‘What is cinema?’ but ‘What is philosophy?’ Cinema itself is a new practice of images and signs, whose theory philosophy must produce as conceptual practice. For no technical determination, whether applied (psychoanalysis, linguistics) or reflexive, is sufficient to constitute the concepts of cinema itself. (280)

Cinema, then, is not simply a representation of, say, Bergson’s ideas about movement and duration; rather, cinema is itself philosophy. But how is it possible for cinema to generate concepts? What would it mean for cinema to constitute a form of knowing that is inaccessible to us—or that we can only grasp with its help or by its means?

One example of a concept that is specific to cinema, and ungraspable without it, is the any-instant-whatever. In the first chapter of Cinema 1 Deleuze identifies a crucial tension within cinema: between the “privileged instant”—moments at which the great directors attempt to extract meaning from the moving image—and the “any-instant-whatever,” the technological basis of the image. This is really an opposition between two forms of perception: the perception of the technical apparatus—the cinema—and the perception of human beings. Referring to Eadweard Muybridge’s early experiments photographing the movements of animals, Deleuze points out the following: if there are privileged instants in Muybridge’s pictures (for example, when the horse has one hoof on the ground, or none), “it is as remarkable or singular points which belong to movement, and not as the moments of actualization of a transcendent form.” Deleuze goes on:

The privileged instants of Eisenstein, or of any other director, are still any-instants-whatever: to put it simply, the any-instant-whatever can be regular or singular, ordinary or remarkable. If Eisenstein picks out remarkable instants, this does not prevent him deriving from them an immanent analysis of movement, and not a transcendental synthesis. The remarkable or singular instant remains any-instant-whatever among the others …. (5–6)

This passage establishes a close relation between the technical specificity of cinema, the apparatus (the fact of a movement-image being constructed out of a succession of “any-instants-whatever,” twenty-four frames per second), and its “soul” (Cinema 1 206). From the beginning, according to Deleuze, cinema is in conflict with itself; the temptation is always there to extract privileged instants from the succession of any-instants-whatever, as in Eisenstein’s “dialectical” cinema but also in every commercial film that is ever made.

Deleuze’s entire thesis on movement is organized around this opposition between the privileged instant and the any-instant-whatever. The essence of cinema is to know—despite what we “know,” despite what its practitioners “know,” despite what Eisenstein “knows”—that there are no privileged instants; or at least, there are privileged instants only insofar as we impose our own interests, our own cuts or disconnections, on the movement image: “As Bergson says, we do not perceive the thing or the image in its entirety, we always perceive less of it, we perceive only what we are interested in perceiving, or rather what it is in our interest to perceive, by virtue of our economic interests, ideological beliefs, and psychological demands. We therefore normally perceive only clichés” (Cinema 2 20). Deleuze presents the emphasis on the any-instant-whatever as an anti-dialectical (that is to say, a non-historicist, non-historical) move. Cinema is the expression of a shift, itself historical, in which meaning and history have ceased to operate dialectically. It is no longer possible, or necessary, to locate a synthesis of the disparate elements or moments in order to give those elements order and closure, to derive meaning from them. The “instants” of cinema are all “equidistant” from one another, and from the whole; no single moment emerges to unify and explain the rest. Insofar as cinema does locate or search for such moments, it is only by fleeing from or suppressing its “essence.” In his essay on Deleuze’s cinema books, Rancière refers to this thesis as Deleuze’s “rigorous ontology of the cinematographic image” (107).

2. The Sensorimotor Schema and its Collapse

Bergson’s contribution to and importance for Deleuze’s cinema books is his discovery of the sensorimotor schema, according to which perception, action and affection are part of the same corporeal system. The first chapter of Bergson’s Matter and Memory describes the interplay of these three elements within the system that he calls “sensorimotor.” Bergson’s theory of perception does not begin, like Descartes, with human perception, but from “the reality of matter,” which is to say, “the totality of its elements and of their action of every kind” (30). Elsewhere he makes clear that the totality of matter can also be described as “the totality of perceived images” (64). Associated with this “totality of elements” is the hypothesis of an order of “pure perception”: “a perception which exists in theory rather than in fact and would be possessed by a being … capable … by giving up every form of memory, of obtaining a vision of matter both immediate and instantaneous” (97). From that starting point, human perception emerges not as something added to matter, but rather, as a gradual limitation of it, as the subject is formed as a center not of determinacy but of “indetermination.” Bergson rejects the idea that our perception produces knowledge of the object perceived (17). Perception is corporeal, which means that it is “subtractive”: it results from “the discarding of what has no interest for our needs, or more generally for our functions” (30). The most direct description of the sensorimotor system in Bergson’s work comes in the opening chapter of Matter and Memory:

Perception, understood as we understand it, measures our possible action upon things, and thereby, inversely, the possible action of things upon us. The greater the body’s power of action (symbolized by a higher degree of complexity in the nervous system), the wider is the field that perception embraces. The distance which separates our body from an object perceived really measures, therefore, the greater or less imminence of a danger, the nearer or more remote fulfilment of a promise. … Consequently, our perception of an object distinct from our body, separated from our body by an interval, never expresses anything but a virtual action. But the more the distance decreases between this object and our body (the more, in other words, the danger becomes urgent or the promise immediate), the more does virtual action tend to pass into real action. Suppose the distance reduced to zero, that is to say that the object to be perceived coincides with our body, that is to say again, that our body is the object to be perceived. Then it is no longer virtual action, but real action, that this specialized perception will express: and this is exactly what affection is. […] Our sensations are, then, to our perceptions that which the real action of our body is to its possible or virtual action. Its virtual action concerns other objects, and is manifested within those objects; its real action concerns itself, and is manifested within its own substance. (57–8)

Perception, action and affection exist, therefore, as mutually constitutive events within the sensorimotor schema.

What does it mean to talk of the collapse of this schema? Deleuze asks the same question in the second chapter of Cinema 2. The answer is found in the possibility of a perception that is no longer organized around “interest” or “needs,” that is to say, around action, whether deferred or real (affection). On the contrary, the “interval” between perception, action and affection is no longer relative or deferred, but becomes absolute. This is the difference that delineates a “modern” from a “classical” cinema:

[F]rom its first appearances, something different happens in what is called modern cinema: not something more beautiful, more profound, or more true, but something different. What has happened is that the sensory-motor schema is no longer in operation, but at the same time it is not overtaken or overcome. It is shattered from the inside. That is, perceptions and actions ceased to be linked together, and spaces are now neither co-ordinated nor filled. Some characters, caught in certain pure optical and sound situations, find themselves condemned to wander about or go off on a trip. These are pure seers, who no longer exist except in the interval of movement, and do not even have the consolation of the sublime, which would connect them to matter or would gain control of the spirit for them. They are rather given over to something intolerable which is simply their everydayness itself. It is here that the reversal is produced: movement is no longer simply aberrant, aberration is now valid in itself. (39–41)

Cinema opens onto the world through the experience of “direct time-images”; this is its revolutionary importance for Deleuze. Examples include the shot of the vase in Ozu’s Late Spring; the anxiety of the characters in Hitchcock’s films, which is expressed in pure “optical situations”—the perception-image of the poisoned glass of milk in Suspicion, the figure of the spiral in Vertigo, the many perception-images in Rear Window; but, also earlier, such famous moments in Italian neo-realism as the girl’s perception of her own pregnant stomach in De Sica’s Umberto D.

The sensory-motor break makes man a seer who finds himself struck by something intolerable in the world, and confronted by something unthinkable in thought. Between the two, thought undergoes a strange fossilization, which is as it were its powerlessness to function, to be, its dispossession of itself and the world. For it is not in the name of a better or truer world that thought captures the intolerable in this world, but, on the contrary, it is because this world is intolerable that it can no longer think a world or think itself. The intolerable is no longer a serious injustice, but the permanent state of a daily banality. (169–70)

What is the “something intolerable in the world,” the “something unthinkable” within thought? It is simply the fact of the discrepancy between thought and the forms available to it; it is unthinkability itself. This might seem tautological. Indeed, for Artaud, writes Deleuze, “Thought has no other reason to function than its own birth, always the repetition of its own birth, secret and profound” (165). But it is not tautological as long as we retain an openness to the idea that, in Deleuze’s work, it is cinema itself that thinks. It is not that cinema enables us to think something other than cinema, but that cinema is itself thought. Cinema has become capable of thinking something that was not thinkable before: the absence of linkages, the break in the sensorimotor schema itself. And that thinkability of the absence of links in cinema must mean that cinema is one of the historical factors behind the destruction of the links themselves.

According to Deleuze, then, cinema establishes a material basis for the realization of Bergson’s hypothesis of a world of “pure perception,” in which perception is coterminous with matter itself. Cinema gives us, directly, a world in which image = movement; that is to say, in which perception = matter; in which, after centuries of philosophy devoted to the problem of their unbridgeable divide, subject and object are brought into real, rather than merely theoretical alliance.

The revolutionary core of Deleuze’s work on cinema is found here, not in the transition from the “movement-image” to the “time-image” signaled in the shift between Cinema 1 and Cinema 2. Cinema, says Deleuze, “is the pure vision of a non-human eye, of an eye which would be in things” (Cinema 1 81).

One of the places where Deleuze deals directly with the effects of the sensorimotor break at the level of the cinematic image is chapter 7 of Cinema 2, devoted to “Thought and Cinema.” Even here the break is a hypothetical proposition; but at least it becomes possible, with the new cinema, to imagine a world in which perception is separate from action; where universal non-human perception (Bergson’s category of pure perception) is possible. The new cinema will be characterized by the proliferation of pure optical and sound situations unconnected to any centered narrative or plot, and by the displacement or suspension of action-oriented movement and action-oriented perception.

For Deleuze it is Jean-Luc Godard, even more than directors such as Carl Dreyer, Robert Bresson and Eric Rohmer, who represents the highest achievement of cinema in producing a cinema not of the idea, or of the positive term, but rather of the “interstice,” a cinema that does away with “all the cinema of Being = is” (180), a cinema of the “unthought in thought,” a cinema that is therefore able to restore “our belief in the world” by filming interstices. In Godard, cinema is itself thought; cinema has liberated itself from the task of representing thought. In Godard there is no “privileged” image or discourse: the “good” discourses of “the militant, the revolutionary, the feminist, the philosopher, the film-maker,” are all treated with the same “categorical” inflection—that is to say, generically. Thought in Godard happens elsewhere than in these representational moments, which is to say that it happens in cinema itself—as cinema.

For Deleuze, the crucial distinction between the work of Dreyer, Bresson and Rohmer, on one hand, and Godard, on the other, is contained in the distinction between two phrases: the whole is the open and the whole is the outside (Cinema 2 179). Both phrases refer to the out-of-field (or out-of-shot). By the whole is the open, what is meant is an out-of-field that “refer[s] on one hand to an external world which was actualizable in other images, on the other hand to a changing whole which was expressed in the set of associated images. “The whole is the open” thus posits an out-of-field that is in continuity with what is in the shot. “The whole is the outside,” by contrast, refers to something like an absolute out-of-field: an out-of-field that has no hope of ever entering the shot. What counts is no longer “the association or attraction of images” but “the interstice between images, between two images.” “In Godard’s method,” writes Deleuze,

it is not a question of association. Given one image, another image has to be chosen which will induce an interstice between the two. … The fissure has become primary, and as such grows larger. It is not a matter of following a chain of images, even across voids, but of getting out of the chain or the association. Film ceases to be “images in a chain … an uninterrupted chain of images each one the slave of the next”, and whose slave we are … It is the method of BETWEEN, “between two images,” which does away with all cinema of the One. It is the method of AND, “this and then that”, which does away with all the cinema of Being = is. Between two actions, between two affections, between two perceptions, between two visual images, between two sound images, between the sound and the visual: make the indiscernible, that is the frontier, visible. …

Just as the image is itself cut off from the outside world, the out-of-field in turn undergoes a transformation. When cinema became talkie … the sound itself becomes the object of a specific framing which imposes an interstice with the visual framing. The notion of voice-off tends to disappear in favour of a difference between what is seen and what is heard, and this difference is constitutive of the image. There is no more out-of-field. The outside of the image is replaced by the interstice between the two frames in the image … Interstices thus proliferate everything, in the visual image, in the sound image, between the sound image and the visual image. … Thus, in Godard, the interaction of two images engenders or traces a frontier which belongs to neither one nor the other. (179–81)

Jafar Panahi’s The Mirror (1997)

It would be relatively easy to talk about Godard’s cinema in relation to this set of claims, for films such as Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1966) or Ici et ailleurs (1976) precede Deleuze’s work on cinema and directly inform it. I would like instead to consider a more recent body of work—produced in quite different historical circumstances—by the Iranian director Jafar Panahi, and within that body of work a scene from his 1997 film The Mirror (Ayeneh).

The question of the conditions of emergence of the so-called “new wave” of Iranian cinema is a complex one, especially its rediscovery and reinvention of the time-image in the period since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. In many ways, the situation of Iran’s filmmakers since the Revolution has been analogous to the one that Deleuze describes in post-war Italy, in that they are neither implicated in the ancien régime nor enjoy ideological or unambiguous material support under the newer one.[iv] Notwithstanding this complexity—a full account of which would have to include the undoubted influence of European art cinema on its stylistic and thematic concerns—the recent history of Iranian cinema dramatizes the same questions with which I began this essay: in particular, of whether the breakage of the sensorimotor links is a historical development or merely a subjective one.

Panahi’s The Mirror concerns a seven-year old girl whose mother does not arrive to pick her up from school one day. The first half of the film is the story of the girl’s attempt to get home by herself; the journey is complicated by the fact that her left arm is in a cast. First, a man with a scooter gives her a ride to the bus stop; she gets on the bus, but it turns out to be going in the wrong direction. Eventually she makes it onto the right bus. And then abruptly, half way through the film, the narrative frame is broken by an apparently unanticipated event: the girl looks directly at the camera, and is addressed by a crew member offscreen: “Mina, don’t look at the camera.” Mina removes her cast, angrily declares, “I’m not acting anymore,” and demands to be let off the bus. Panahi, directing the film, and other crew members enter the frame as they try to reason with her, but she is intransigent. The director decides to allow her to make her own way home. Mina has not removed her microphone, and the crew continues to film as she walks away. We see and hear as she tries and fails to take a taxi; she has various conversations, including one with an actor, an older woman, with whom she has interacted as a character in the earlier part of the film; finally she takes another taxi that will carry her part of the way. We hear the conversation among the other passengers inside the taxi, while the film crew follows in another car (fig. 1). And then, in a heavy traffic jam, she gets out of the taxi and we (that is to say, the camera), fifty feet behind, lose sight of her. All we hear is her feet pattering down the street as the soundtrack becomes entirely disconnected from the image onscreen.

Fig. 1. The Mirror (Ayeneh), dir. Jafar Panahi, Rooz Film, Iran, 1997.

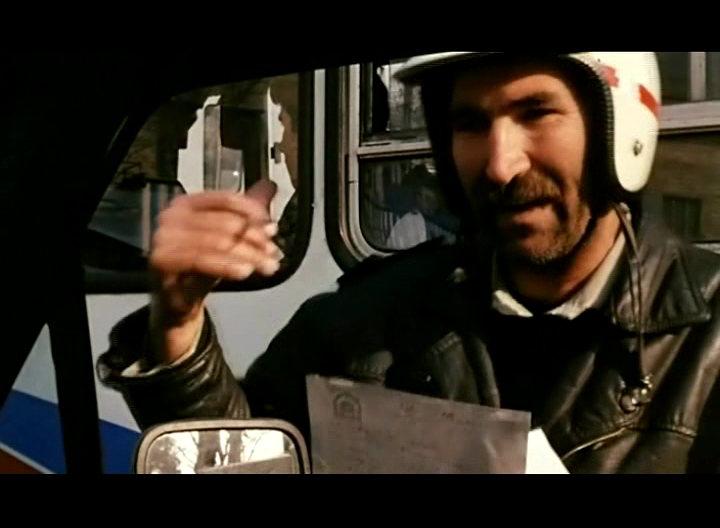

The sequence during which Mina is out of view of the camera lasts for 6 or 7 minutes. A traffic policeman in a white helmet approaches the car, and a conversation takes place with the driver through the passenger window (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The Mirror (Ayeneh), dir. Jafar Panahi, Rooz Film, Iran, 1997.

The only sound is from the microphone attached to Mina, so we hear nothing of what is said in the conversation with the policeman, only the noise of people watching a football match between Iran and South Korea as Mina apparently walks past a café. After a few minutes, the film crew again catches up with Mina who, meanwhile, has been conversing with a man who has worked in the Iranian film industry, dubbing John Wayne into Farsi. As Mina again comes into view of the camera, she is standing on the curb waiting for her brother to meet her.

So, what do we see in this seven-minute sequence? Is this a film of the interstice, as Deleuze says of Godard’s cinema? What or where is the whole? Should we say the whole is the open (continuous with the action onscreen) or the whole is the outside (discontinuous with it and unavailable to the cinematic image)? How should we conceptualize the out-of-field in this sequence, as relative or absolute? Can we say, with Deleuze, that the out-of-field is abolished, that the “outside of the image” is replaced by “the interstice between the two frames in the image,” that is, by “the difference between what is seen and what is heard”? Can we say that this difference is “constitutive of the image”? Or is it the case that, on the contrary, there is no justification for dispensing with the out-of-field, that the primary organization of the image remains sensorimotor? If, as Deleuze notes, the objection that an interstice can only take place between associated images is merely “proof that we are not yet ready for a true ‘reading’ of the visual image” (Cinema 2 179), what basis do we have in sequences such as this for continuing to strive for or even imagine the possibility of such a “true ‘reading’”?

There is no way to resolve these questions, and yet it is on them that the dialogue between Rancière’s and Deleuze’s work turns.

Rancière’s Critique

Rancière’s essay on Deleuze’s cinema books, entitled “From One Image to Another: Deleuze and the Ages of Cinema,” offers one of the most concise overviews of Deleuze’s cinema project available. Rancière characterizes Deleuze’s theory of the sensorimotor break as follows: “Thenceforward, what creates the link is the absence of the link: the interstice between images commands a re-arrangement from the void and not a sensory-motor arrangement” (108). But Rancière goes on to construct a strong critique of Deleuze, predicated in part on the ambiguity of Deleuze’s historical thesis about the shift from the movement-image to the time-image.

There are several emblematic moments in Rancière’s critique—emblematic because they turn out to be principles of Rancière’s general reading of Deleuze, in which the “rupture” in the sensorimotor schema is shown to be amenable to, indeed complicit with, the links of narrative. Wherever instances of the crystal-image, or the disruption of the sensorimotor schema, appear, Rancière suppresses their radicalism by re-inserting them into a narrative logic, re-establishing their sensorimotor function. By such means, Rancière will argue that Deleuze’s “classical” cinema, participating in a “logic of the movement-image,” and “modern” cinema, “the logic of the time-image,” are both “indiscernibly” part of the aesthetic regime: “Cinema is the art that realizes the original identity of thought and non-thought that defines the modern image of art and thought” (122).

Thus, in his account of Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera, Rancière disputes the proposition that Vertov’s camera attempts to (as Deleuze has it) “put perception into things, to put perception into matter, so that any point whatsoever in space itself perceives all the points on which it acts, or which act on it …” For Rancière it is not at all clear that this is what Vertov was trying to do; the implication is rather that Vertov’s camera attempts “to join all spatial points at the center it constitutes” (110). Rancière claims that the real significance of the moments that Deleuze finds important in Man With a Movie Camera—moments of looking—is primarily a narrative significance: “Every image in Man with a Movie Camera ultimately points back to the persistent representations of the omnipresent cameraman with his machine-eye and of the editor whose operations alone can breathe life into images inert in themselves” (110). Vertov’s film for Rancière, then, is simply a narrative of two men travelling around Odessa shooting a film.

A second emblematic moment occurs in Rancière’s reading of Hitchcock’s Vertigo. In the last chapter of Cinema 1, Deleuze writes of the rare moments in Hitchcock where the hero is caught living in “a strange state of contemplation.” His examples include the photographer-hero who has broken his leg in Rear Window and the inspector in Vertigo (both played, incidentally, by James Stewart). Both characters, for different reasons, are reduced to “a state of immobility” and thus to “a pure optical situation” (205). In each case, a narrative explanation for the paralysis is provided by the diegesis; yet such moments, says Deleuze, anticipate the “crisis” of the movement-image that will happen only “in [Hitchcock’s] wake” (205).

As with Man With a Movie Camera, Rancière rejects Deleuze’s reading: “[Scottie’s] vertigo doesn’t hinder in the least, but rather favors the play of mental relations and of ‘sensory-motor’ situations that develop around these questions” (115). In such passages, writes Rancière, Deleuze “turns against Hitchcock the fictional paralysis that the manipulative thought of the director had imposed on his characters for his own expressive ends. Turning this paralysis against Hitchcock amounts to transforming it, conceptually, into a real paralysis” (116). This is the approach that will lead to Rancière concluding (via an ingenious analysis of Bresson’s Au hazard, Balthazar) that Deleuze’s reading of such works is dependent upon an “allegorical” extension of such narrative elements into the metaphysical sphere.[v] For Rancière, Deleuze’s reading of Hitchcock imports an absolute out-of-field—that is, a transcendental principle—into a text whose out-of-field is never anything other than strictly relative. Ultimately, for Rancière, the collapse of the sensorimotor schema in post-war cinema never takes place. In every case, what appears to be a proliferation of optical or sound situations are situations of narrative (or narrativizable) “paralysis” that are perfectly comprehensible within, and often central to, the “expressive” intentions of the director.

These alternative readings of Man With a Movie Camera and Vertigo are undecidable; and the same could be said of Panahi’s The Mirror. There is certainly a coherent narrative to be excavated out of The Mirror. Reading it as Rancière might read it we could say that the film opens with a false frame—the story of the little girl whose mother has forgotten to pick her up from school—only to reveal, half way through, that the first story was simply a story within a story. The real story of The Mirror concerns the making of a film about a little girl named Mina, played by an actress who also happens to be called Mina. But in order to hold to that account of the film; in order to reject the thesis of the breakdown or the collapse of the sensorimotor schema that underpins the exceptionality of cinematic thought in Deleuze’s cinema books; in order to claim that the “interval” between the two girls in The Mirror is merely a narrative one, not a philosophical one; in order to retain the sense of cinema as a medium of thought, rather than a substratum of it, a “mediator”—the simple fictionality of the work would have to be shown to be beyond doubt. Writing about Tod Browning’s film The Unknown, and taking issue with Deleuze’s account of it, Rancière declares: “It is very difficult to specify, in the shots themselves or in their sequential arrangement, the traits by which we would recognize the rupture of the sensory-motor link, the infinitization of the interval, and the crystallization of the virtual and the actual” (118). In the case of The Mirror, however, the reverse is true, for it seems impossible to determine “in the shots themselves or in their sequential arrangement” the traits by which we could be assured of their fictional (i.e., purely narrative) significance, that is to say, of the merely “aesthetic” intentions of the filmmaker, the merely “paradoxical” quality of Mina herself.

Deleuze’s hypothesis of the sensorimotor collapse seems to involve an acceptance of the idea that, as Deleuze puts it, “we are not yet ready for a true ‘reading’ of the visual image” (180). The hypothesis is hostage to an imagined future evolution of cinema in which the elimination of the narrative alibi of the time-image might be achieved. If, as Rancière proposes, and as even Deleuze at times seems to suggest, the sensorimotor collapse has not (yet) taken place, how can we avoid the conclusion that its prominence in post-war cinema is not a historical but an aesthetic, or a theoretical, proposition? A decisive moment in Rancière’s critique of Deleuze comes with his proposition that the distinction between the movement-image and the time-image (or, as Rancière calls them, the “matter-image” and the “thought-image”) is “strictly transcendental” precisely because it is not grounded in history, in the “natural history of images” (114). There is, for Rancière, no “identifiable rupture, whether in the natural history of images or in the history of human events or of forms of the art of cinema.”

And yet, the premise of Deleuze’s analysis of cinema is not that cinema is the medium of the sensorimotor collapse but that cinema has taught us to think the rupture of the sensorimotor link, the “infinitization” of the interval, which is to say the inseparability of the virtual and the real. The event of the sensorimotor break is not its actualization but its thinkability. After cinema, the chronological hypothesis according to which the sensorimotor break is a historical moment forever dividing a cinema of “matter” from a cinema of “thought” is no longer feasible. It is cinema, however, not Rancière (or Deleuze), that teaches us that. Rancière concludes his essay by noting the “near-total indiscernibility between the logic of the movement-image and the logic of the time-image” (122); but, far from undermining Deleuze’s project, this is its crucial lesson.

The truly revolutionary moment in Deleuze’s cinema project is not the historical claim of a sensorimotor collapse, but the proposition, grounded in the reading of Bergson, that cinema is the form in which Bergson’s hypothesis of “pure perception” dispenses with its limitations as a hypothesis. This event is achieved not in the course of cinema’s development but with the earliest works of cinema. The moment at which “movement is no longer simply aberrant [but] is now valid in itself” is not dependent on some real or hypothetical development of cinema; it is there from the beginning, indeed, before a single shot has been produced.

The real revolution is thus Bergson’s sensorimotor hypothesis itself, the first modern theory of the distribution of perception. The theory of the sensorimotor schema is simultaneously the collapse of the schema, the moment when perception is revealed to be determined by nothing other than interest. The sensorimotor collapse is not the event that divides cinema into classical and modern, but the condition of possibility of cinema as such—cinema conceived not as a medium but as a practice. The sensorimotor collapse has always already taken place: before Deleuze, before Rancière, and before the claims of both, very different in inflection, that it has not.

Footnotes

[i] In an interview given shortly after the publication of Cinema 2, Deleuze was asked about the principles behind the “changes” in the cinematic image, and consequently, about the “basis” upon which we can assess films. His response was to situate the changes biologically: “I think one particularly important principle is the biology of the brain, a micro-biology. It’s going through a complete transformation and coming up with extraordinary discoveries. It’s not to psychoanalysis or linguistics but to the biology of the brain that we should look for principles, because it doesn’t have the drawback, like the other two disciplines, of applying ready-made concepts. We can consider the brain as a relatively undifferentiated mass and ask what circuits, what kinds of circuit, the movement-image or time-image trace out, or invent, because the circuits aren’t there to begin with” (Negotiations 59-60).

[2] In Critique of Judgment, for example, Immanuel Kant describes the aesthetic idea as one “to which no determinate thought whatsoever, i.e., no concept, can be adequate, so that no language can express it completely and allow us to grasp it” (182; §49).

[3] Rancière articulates these two problems as follows: “First of all, how are we to think the relationship between a break internal to the art of images and the ruptures that affect history in general? And secondly, how are we to recognize, in concrete works, the traces left by this break between two ages of the image and between two types of image?” (108)

[4] Adam Bingham writes: “The very strictures placed by [Khomeini’s] government on cinematic representation had a direct effect on this new aesthetic, as they were forced to approach their subjects and themes obliquely, indirectly, through inference and allusion” (169). Bingham goes on to characterize the period as “a cinematic new beginning as marked as that which took place in society” (170).

[5] Rancière’s insistence upon an allegorical basis to Deleuze’s reading of Au hazard, Balthazar has two aspects. The first relates to Deleuze’s conception of the relation between cinema and thought, which is for Rancière not directly philosophical but allegorical (116, 119); thus, “the rupture of the sensory-motor link” is an idea not of cinema but of Deleuze himself, and not an event in the history of thought but an object of Deleuze’s philosophical imagination. Second, Bresson’s film suggests itself to Rancière as an allegorical lesson in the evasions of Deleuze’s philosophy of cinema, and thus, in the persistence of the sensorimotor schema in the very moment of its collapse. In Rancière’s reading, the manipulative character Gérard, who pursues Marie with a succession of traps and schemes, stands in for Hitchcock, “the manipulating filmmaker par excellence” (116), and is contrasted with Bresson himself, the filmmaker of the sensorimotor break. The problem is that this “bad filmmaker,” observes Rancière (mischaracterizing the place of Hitchcock in Deleuze’s analysis) “is uncannily like the good one.” The “visually fragmented shots and connections” in Bresson’s work that, for Deleuze, reveal “the power of the interval,” for Rancière amount to nothing more than a narrative ellipsis, “an economic means of bringing into sharp focus what is essential in the action” (122).

Works Cited

- Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory. Trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1997. Print.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. Problems in Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Trans. Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1984. Print.

- Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. Trans. Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer. New York: Macmillan, 1911. Print.

- Bingham, Adam. “Post-Revolutionary Art Cinema in Iran.” Directory of World Cinema Volume 10: Iran. Ed. Parviz Jahed. Bristol: Intellect, 2012. Print.

- Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. London: Athlone, 1986. Print.

- —————. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. London: Athlone, 1989. Print.

- —————. Negotiations, 1972–1990. Trans. Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia UP, 1995. Print.

- —————. “What is the Creative Act?” Two Regimes of Madness: Texts and Interviews 1975–1995. Trans. Ames Hodges and Mike Taormina. New York: Semiotext(e), 2006: 312–324. Print.

- Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgment. Trans. Werner S. Pluhar. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987. Print.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life.” Untimely Meditations. Trans. R. J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

- Rancière, Jacques. Film Fables. Trans. Eliliano Battista. Oxford: Berg, 2006. Print.

- —. The Politics of Literature. Trans. Julie Rose. Cambridge: Polity, 2011. Print.